- Home

- Sponsors

- Forums

- Members ˅

- Resources ˅

- Files

- FAQ ˅

- Jobs

-

Webinars ˅

- Upcoming Food Safety Fridays

- Upcoming Hot Topics from Sponsors

- Recorded Food Safety Fridays

- Recorded Food Safety Essentials

- Recorded Hot Topics from Sponsors

- Food Safety Live 2013

- Food Safety Live 2014

- Food Safety Live 2015

- Food Safety Live 2016

- Food Safety Live 2017

- Food Safety Live 2018

- Food Safety Live 2019

- Food Safety Live 2020

- Food Safety Live 2021

- Training ˅

- Links

- Store ˅

- More

Advertisement

Featured Implementation Packages

-

BRCGS (& FSMA) Food Safety and Quality Management System for Food Manufacturers - Issue 9

This comprehensive yet simple Food Safety Management System Package contains EVE... more

-

Advanced HACCP System for Food Manufacturers

Our HACCP package completely simplifies the process of implementing a HACCP syst... more

SQF from Scratch: 2.1.3 Management Review

Jan 30 2020 06:45 PM | Simon

SQF 2.1.3 management review

2.1.3 Management Review

These first few elements established the relationship site management needs to have with the food safety system. SQF is not just an exercise for the practitioner.

First, we had management identify that food safety is part of our business mission, not just something we have to do.

Then, we made them put their money where their mouth is by designating an SQF practitioner and showing employees how the top levels of the company are ultimately responsible for that mission.

Now, we need to make sure that long after we’ve created these policies, the people in charge are going to receive the information needed to uphold that responsibility every day, long after we’ve attained certification. We’re also going to make sure that this system stays alive, and doesn’t become a binder on the shelf that just gets whipped out when the auditor arrives, and no one at the company has any idea what’s inside.

The code:

2.1.3 Management Review

2.1.3.1 The senior site management shall be responsible for reviewing the SQF system and documenting the review procedure. Reviews shall include:

i. The policy manual;

ii. Internal and external audit findings;

iii. Corrective actions and their investigations and resolution;

iv. Customer complaints and their resolution and investigation;

v. Hazard and risk management system; and

vi. Follow-up action items from previous management review.

2.1.3.2 The SQF practitioner(s) shall update senior site management on a (minimum) monthly basis on matters impacting the implementation and maintenance of the SQF system. The updates and management responses shall be documented. The SQF system in its entirety shall be reviewed at least annually.

2.1.3.3 Food safety plans, good manufacturing practices, and other aspects of the SQF system shall be reviewed and updated as needed when any potential changes implemented have an impact on the site’s ability to deliver safe food.

2.1.3.4 Records of all management reviews and updates shall be maintained.

What’s the point? How is this making our product safer?

“Oh my goodness”, you may think, “we have to review EVERYTHING at least once a YEAR?”

Yes.

I spend a lot of my time working with QA departments on making their systems more flexible, easier to maintain, and reduce overall paperwork because unnecessary clerical work hurts our ability to make safe food (even if it makes it look like we are).

But that’s just it, we want to make systems that follow our golden rule, which means we use them and we integrate them. We review them constantly to make sure that nothing has become obsolete.

We review them to make sure that they still make sense to our business.

We review them to make sure the science is still holding up.

We loosen requirements for things that are no longer an issue and tighten them for things that are affecting our customers.

And an SQF practitioner who is ready to demonstrate how they attain food safety, not just provide a bunch of forms that say they do, needs to be an expert in their own policy manual.

What’s the point of an SQF practitioner, not to mention a company point person for audits, if they don’t know their own systems backwards and forwards? Knowing how all of the pieces of the system connect together not only helps avoid creating redundant waste, it also shows where there are gaps.

What am I being asked to do?

So, what’s a review? It depends.

Policy Manual and Hazard and risk management system (food safety plan)

For a “policy manual”, a.k.a. the “register” of controlled policies, procedures, and food safety plan that make up the system; the review is of the system rather than its outputs.

The review of a policy manual document (SOP, Policy, Procedure, Food Safety Plan) should entail:

- A complete read-through by the SQF practitioner

- The opportunity for stakeholders in the procedure to review or request any revisions

- Note: Stakeholders change, not everyone needs to see the waste management SOP, but top levels do need to see the food safety plan

- If no changes, documentation that the review actually took place.

Depending on the company’s level of integration and support in the SQF system, those other stakeholders in the policy may not actually thoroughly review things. That’s not ideal but does not stop a practitioner from making helpful documents. As long as their own review is thorough and they audit whether those policies and procedures are actually followed, the documents stay alive and relevant.

Never make systems to “pass audits”. Make systems that work for your company that help it make safer/higher quality products more efficiently.

This can be very tough for some quality personnel to grasp, as they may have been in a quality environment where their performance is based on auditing or “making sure we follow the code”. That’s a management error. If there is a company issue where a policy requirement does not have good follow through or buy-in from other departments, it needs to be adopted or dropped. It turns out that when quality personnel spend time doing those tasks (usually by spending time in production), not just asking for them to be done, or when they have to actually draw lines in the sand for everything they specify in an SOP, those “auditable” things in documents tend to go away, making them better documents that support the most critical components.

As each document is reviewed, the practitioner should ask and answer these questions:

- Does this document still support it’s intended purpose?

- Do we actually practice this document as written without exceptions?

- Are any of the requirements/procedures obsolete?

- Are any of the justifications obsolete?

- Is new information available that should change how we do things (e.g. complaint trending, internal audits, industry changes)?

Some auditors may disagree. That’s okay, their responsibilities are different than ours.

This doesn’t eliminate the reality that we need to make sure the SQF code is supported by our policy manual. Heck, that’s the entire point of this article series! So how to we get this taken care of?

My recommendation is that practitioners conduct a separate, annual review using the SQF checklist. This review is the one everyone is more familiar with, but it’s less important than what we discussed above, where we review the efficacy of our systems rather than conformance to code.

For this review, examine each individual clause in the code, and make sure it’s supported within all of the various documentation in the policy manual and records. This review does not need to include anyone but the audit team, and should be used as an opportunity to prepare for the audit. The intent is to make sure all of the elements are actually covered somewhere in the system. Not by copying and pasting them, but by showing that the company has incorporated them into their own policies and procedures.

This review has the secondary benefit of documenting itself in an auditor friendly way (using the checklist). I like to use it as a training opportunity for backup auditors or folks wanting to learn the code better, and it can be run like a mock/practice audit.

Documenting policy manual reviews

Documentation can be extremely varied, but it’s important to make sure that time is only spent recording information that may be helpful in the future, avoiding documentation for documentation’s sake.

Proof of review of a policy can be accomplished in several common ways:

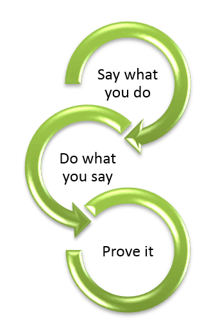

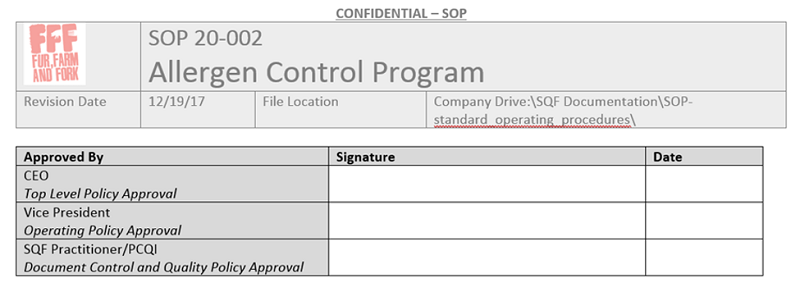

1. The classic revision table at the end of the document

Simple, to prove things are reviewed, just put it in the document itself. This is super common, but somewhat cumbersome. In this setup, in order to verify that every document has been reviewed, every document needs to be inspected. Further, this table is just one more place where errors can occur when new revisions are created (woops, forgot to add the changes!).

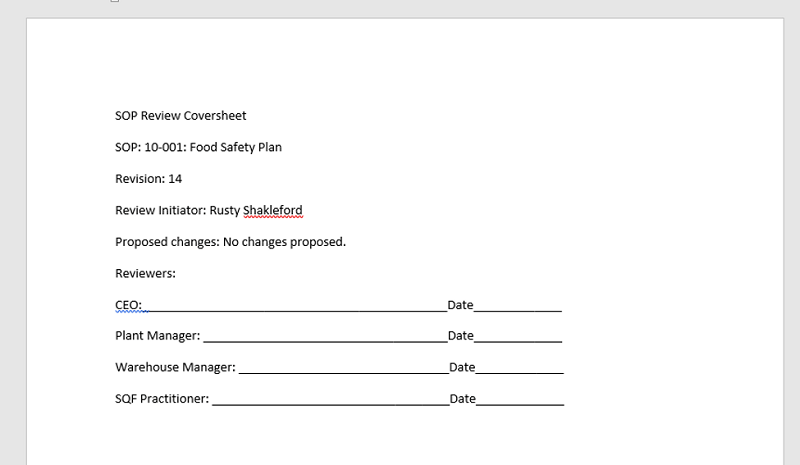

2. The review coversheet

Some organizations get a step closer and think, “Our pest control policy is good to go, so why go through the effort of issuing a new revision? Let’s document that everyone took a look at it and keep that on file instead!”. It’s not bad, but if we’re documenting something with everyone’s signature on it already, all we’ve done is created two documents that need to be archived, the SOP’s and the reviews. Plus, if changes WERE made, the same amount of work needs to be done, but now it requires two sets of signatures instead of one. Seasoned document controllers know that the time it takes to issue new revisions is not consumed by the editing time, but trying to get all of the approvals.

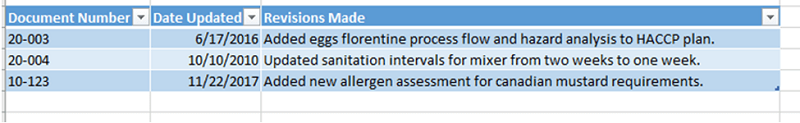

3. New revisions & the review database

This is going to cover most of our review documentation needs. As far as timing, going by previous approval dates reviews should naturally happen on a rolling schedule. This makes sense from a business practicality stand point, but occasionally auditors will get fixated on the statement in 2.1.3.2, “The SQF system in its entirety shall be reviewed at least annually,” and expect some sort of master review that happens once a year. This is worth arguing over since a simultaneous review of everything is both impractical and supports the idea that we shouldn’t ALWAYS be reviewing these policies. However, if you did do the SQF checklist review with your audit team, you can show it to the auditor and be done with it.

Audit findings, corrective actions, complaints, investigations, follow up items

This group of materials to review are the outputs of your system. Like we discussed above, the point of this clause is to make sure that management has the information necessary to support the food safety mission and allocate resources accordingly. This means that critical information from the QA teams needs to be presented to them, at a minimum monthly.

Often management teams meet more often, which is excellent! The tricky non-conformance catch here tends to be due to the lack of documentation of these meetings. Not every meeting has or needs minutes, especially if your QA update is something as simple as “no complaints or issues this week”. Taking the time to write up minutes that cover every word of 2.1.3 is tedious and cumbersome.

Any time we use our scarce minutes or hours to put something together, just so it can be reviewed in seconds by an auditor, it had better be useful to the company and its food safety systems. AKA it should follow our golden rule.

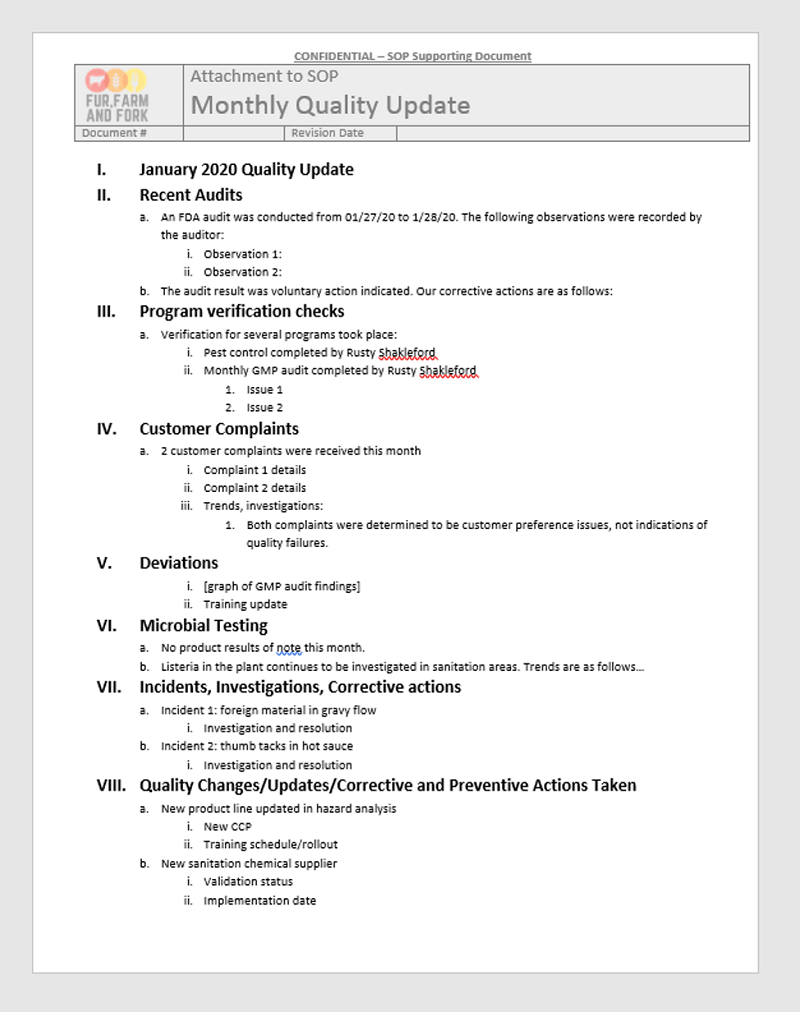

Instead of documenting every individual meeting with management) where multiple topics are discussed and actions are often delegated to other levels), put together a monthly digest of pertinent QA information and distribute it to ANY stakeholder that would be interested. Here’s an example of what such a review could look like:

Compared to how I usually coach documentation, this one does take some time to put together, especially if individual programs don’t have a lot of automated or simple reporting built in. However, it’s a crazy valuable tool to meet a TON of documentation/communication requirements in the code (across multiple elements, thus consolidating paperwork), and it’s very helpful to communicate not only what’s going on in quality to multiple teams, but also the value the quality team is adding to the company.

Sometimes QA works in the background and has a hard time demonstrating that work is being done, this report is a communication tool to show the value QA personnel are adding to the facility in a real way. This leads to better buy in and understanding from other departments. Heck, paper copies can be provided to the entire production floor or have portions shown in a breakroom posting for anyone interested.

How this form is constructed is entirely up to each company, as the focus areas are going to change based on challenges and product categories. If other system outputs (like complaint tracking) already have good databases for trending and reporting, it can be incredibly quick to put together. The key is to keep it simple for a lay audience. It isn’t an internal QA document, it’s for the CEO, plant manager, marketing manager, or whomever to understand what QA is currently doing to make the products safer and higher quality.

The review procedure

We do need to document how these reviews are intended to be performed. But it doesn’t need to be extremely explicit as long as we can, as always, demonstrate that it’s happening. I’ll typically have an SOP called “internal audit” which is intended to cover the policy portions of 2.5.5. In that SOP, I’ll specify the creation of the monthly report outlined above.

Example:

1. Management Updates

a. Every 30-40 days, senior management shall receive an “Monthly Quality Update” that covers matters impacting the implementation and maintenance of the SQF system.

That’s all you need! When crafting the policy it is not necessary to copy the language of the code as long as the monthly update includes all of the information the code requires (like in the above example).

For policy and procedure reviews, I’ll typically include this policy in my document organization/control SOP that supports the recordkeeping and review requirements of section 2.2. I’ll include a tidbit like this one:

1. Review procedure:

a. SOPs shall be routed for revisions/review at least annually.

How will this be audited?

At a minimum, as the auditor goes through each of the policies and procedures, they’re going to look for a document revision change or review within the last 12 months. It’s often not a big deal if one or two are “out of date” by a month or so, especially if a draft is making the rounds. However, if all of them are in that window, it demonstrates that reviews are only taking place around the audit, which doesn’t look great.

Reasons for changes need to be available, but are typically only looked at critically when they are justifications for changing requirements or specifications. E.g. if you started to clean something only every 48 hours instead of 24, that’s a change that needs justification documented.

Changes to process flows or other aspects of the food safety plan will need to have new validations etc. in place to justify the change. If they’re missing this, it often becomes a non-conformance in 2.4.3. But if it’s a matter of there being no record of the new product line getting an analysis at all, it technically would fall under management review. The first example is a failure to follow HACCP principals, the second is a lack of review to make sure the food safety plan stays relevant.

Auditors will seek evidence that management updates turn into actions. If the monthly reports have been getting done, they should also include corrective actions and changes driven by management in response to previous versions of the report. This is a tricky auditing nuance, because auditors love lists and columns. They want to see a form that has: finding, response, who’s responsible, timeframe, time completed, issue closed.

You don’t have to do this again and again on paper, and you shouldn’t. Continuous improvement is just that, continuous. The documentation exists if they’re consistently included in the reports, and the practitioner needs to be able to guide the auditor through the narrative.

Have one or two solid examples ready for the audit. If there was an increase in complaints for labels falling off products, show the progression of that in the monthly updates!

- One month showed a complaint increase and an investigation.

- The next month a corrective action.

- The next month shows a note that QA implemented the new supplier/quality check/machine/whatever that was needed.

- The next month shows how the complaints trended down.

If you can’t think of examples, you’re either not giving yourself enough credit for the improvements you’ve made, or your company is not continuously improving. Usually it’s the former.

2.1.3 does one thing effectively. It demonstrates whether a bunch of documents were created solely to get the SQF certification and keep it, or if SQF elements were integrated into the quality system. Companies who do not meet the elements of 2.1.3 have the following characteristics:

- Only the SQF practitioner knows where the policies are

- Only the SQF practitioner can lead an audit

- The food safety plan hasn’t changed since it was made

- Management has no idea what QA does day to day

- SOP’s contain procedures that aren’t followed and forms that aren’t used (the binder is bloated)

- SQF practitioners don’t remember what all their procedures are during the audit, or perhaps where to find them

Author Biography:

Austin Bouck is a food safety consultant and manufacturing supervisor in Oregon, USA. You can find more food safety resources and discussion on his website, Fur, Farm, and Fork, as well as contact information for consulting services.

1 Comments

These write ups are great. I linked them to our quality guys across the globe, most of which are in the process of SQF certification (China just recently finished).

This will be a great help to them, thanks Austin.