- Home

- Sponsors

- Forums

- Members ˅

- Resources ˅

- Files

- FAQ ˅

- Jobs

-

Webinars ˅

- Upcoming Food Safety Fridays

- Upcoming Hot Topics from Sponsors

- Recorded Food Safety Fridays

- Recorded Food Safety Essentials

- Recorded Hot Topics from Sponsors

- Food Safety Live 2013

- Food Safety Live 2014

- Food Safety Live 2015

- Food Safety Live 2016

- Food Safety Live 2017

- Food Safety Live 2018

- Food Safety Live 2019

- Food Safety Live 2020

- Food Safety Live 2021

- Training ˅

- Links

- Store ˅

- More

Advertisement

Featured Implementation Packages

-

FSSC 22000 Food Safety Management System for Food Service - Version 5.1

This is a tailor-made food safety management system implementation package for C... more

-

SQF Fundamentals Implementation Package for Food Manufacturers

This documentation package is available for immediate download and is perfect fo... more

SQF from Scratch: 2.1.2 Management Responsibility

Jan 12 2020 06:15 PM | Simon

SQF 2.1.2 Management Responsibility

Remember, the goal is not “Audit ready 365”, it’s to know that our facility embraces globally recognized best practices to maintain food safety. Because of this, as we dive into each element, we must always remember the quality management system golden rule: Never make systems to “pass audits”. Make systems that work for your company that help it make safer/higher quality products more efficiently.

2.1.2 Management Responsibility

Following right up on commitment. In addition to identifying our mission of food safety, we also need to determine who will be held accountable for that mission. Where does the buck stop? How are we going to make sure that our new commitment to food safety isn’t just a plaque on the wall, but is a living, breathing (and costly) endeavor?

Some things will be a paperwork exercise, sure, after all everything important happens on paper. But we also need evidence that we have used the time and resources necessary to make sure that competent people, with the right expertise, are making our food safety plan a reality.

The code:

2.1.2 Management Responsibility

2.1.2.1 The reporting structure describing those who have responsibility for food safety shall be identified and communicated within the site.

2.1.2.2 The senior site management shall make provision to ensure food safety practices and all applicable requirements of the SQF System are adopted and maintained.

2.1.2.3 The senior site management shall ensure adequate resources are available to achieve food safety objectives and support the development, implementation, maintenance, and ongoing improvement of the SQF System.

2.1.2.4 Senior site management shall designate an SQF practitioner for each site with responsibility and authority to:

i. Oversee the development, implementation, review, and maintenance of the SQF System, including food safety fundamentals outlined in 2.4.2, and the food safety plan outlined in 2.4.3.

ii. Take appropriate action to ensure the integrity of the SQF system; and

iii. Communicate to relevant personnel all information essential to ensure the effective implementation and maintenance of the SQF System.

2.1.2.5 The SQF practitioner shall:

i. Be employed by the site as a company employee on a full-time basis;

ii. Hold a position of responsibility in relation to the management of the site’s SQF System;

iii. Have completed a HACCP training course;

iv. Be competent to implement and maintain HACCP based food safety plans; and

v. Have an understanding of the SQF Food Safety Code and the requirements to implement and maintain SQF System relevant to the site’s scope of certification.

2.1.2.6 Senior site management shall ensure the training needs of the site are resourced, implemented, and meet the requirements outlined in system elements, 2.9, and that site personnel have met the required competencies to carry out those functions affecting the legality and safety of food products.

2.1.2.7 Senior site management shall ensure that all staff are informed of their food safety and regulatory responsibilities, are aware of their role in meeting the requirements of the SQF food safety code, and are informed of their responsibility to report food safety problems to personnel with authority to initiate action.

2.1.2.8 Job descriptions for those responsible for food safety shall be documented and include provision to cover for the absence of key personnel.

2.1.2.9 Senior site management shall establish processes to improve the effectiveness of the SQF System to demonstrate continuous improvement

2.1.2.10 Senior site management shall ensure the integrity and continued operation of the food safety system in the event of organizational or personnel changes within the company or associated facilities.

2.1.2.11 Senior site management shall designate defined blackout periods that prevent unannounced re-certification audits from occurring out of season or when the site is not operating for legitimate business reasons. The list of blackout dates and their justification shall be submitted to the certification body a minimum of one (1) month before the sixty (60) day re-certification window for the agreed up on unannounced audit.

What’s the point? How is this making our product safer?

If you follow companies who either have large outbreaks or legal action, a common thread tends to be that company representatives blame a lack of information or appreciation for the details necessary to make good food safety risk management decisions. They respond to regulators with their hands up in the air saying things like:

- Wait, there are regulations covering a product like this?

- We’ve never gotten sick and we’ve been eating our own foods for years.

- Hey, nothing is 100%.

- It must have been someone else.

- But we use only the best ingredients.

- Our test results don’t say what yours do.

- We’ve never heard of this requirement.

- It hasn’t been a problem before.

- I don’t understand what you want us to do, we don’t know how to fix this.

What am I being asked to do?

This one’s a pretty stout element with a lot of details, so let’s break it down line by line.

2.1.2.1 The reporting structure describing those who have responsibility for food safety shall be identified and communicated within the site.

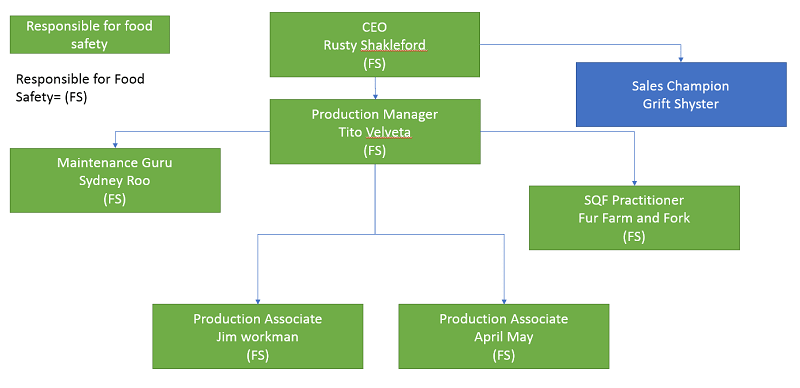

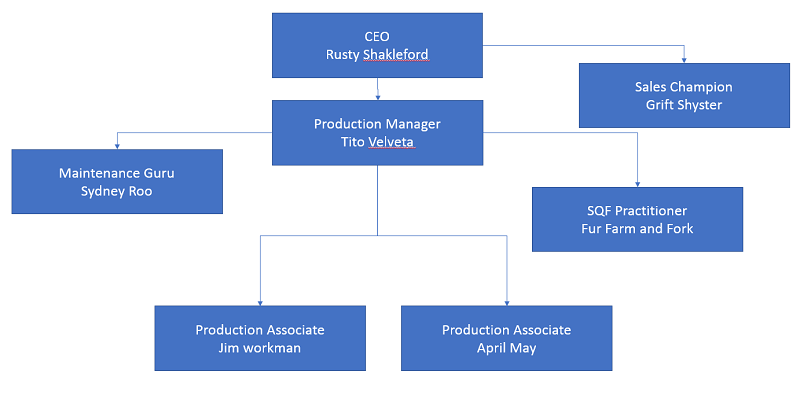

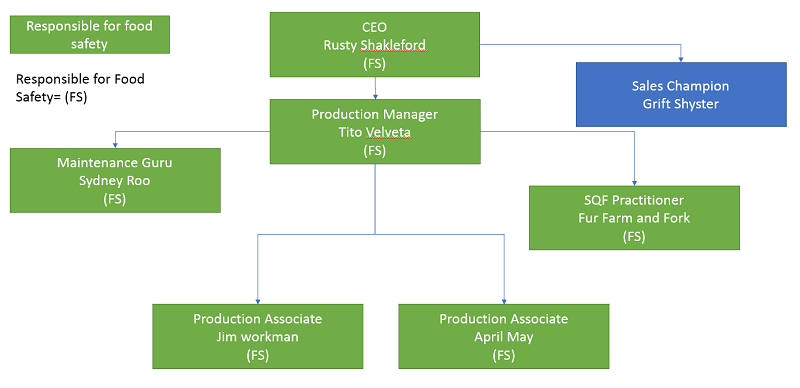

Your business probably already has an organizational chart showing reporting structure, so this one is nearly done! What SQF wants to see is that you know who is responsible for food safety.

It’s not just the Manager or SQF practitioner!

Food safety responsibility mostly falls on the production floor. Floor employees need to know they are the first and most important element in this system. After that, they need to know who’s head to go over when they have a food safety concern. Identifying this in your reporting structure can happen in a variety of ways. My favorite is placing it directly in the org chart.

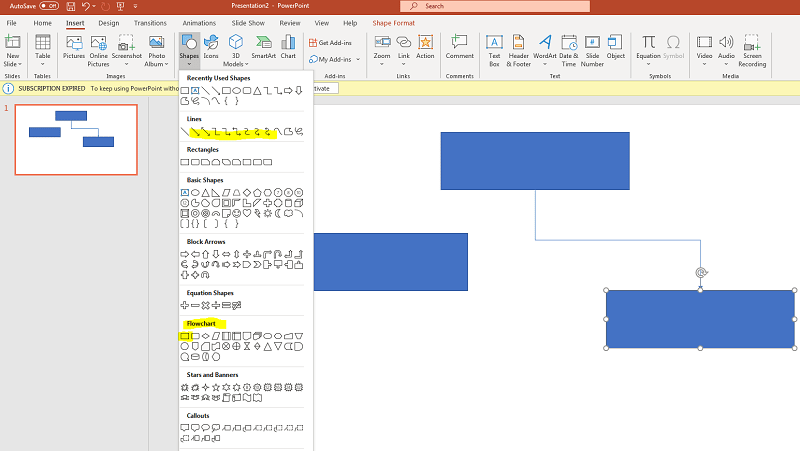

If you need an org chart, there are a million different tools to make one. I typically recommend one in particular, since most employers already have it on site and it’s a surprisingly powerful tool, Microsoft PowerPoint.

Despite there being a dedicated flowchart tool in Microsoft Visio, that’s another license to buy for every user that needs access. Dynamic flowchart shapes are available in PowerPoint with many of the same controls, and PowerPoint generates vector images that can be printed clearly in any size.

You can find the flowchart tools when you go to “shapes” on the insert ribbon.

The connector arrows once connected to flowchart shapes will stay connected when moved around or resized, just like Visio, all you need to do now is fill in the names and titles like this example below:

2.1.2.2 The senior site management shall make provision to ensure food safety practices and all applicable requirements of the SQF System are adopted and maintained.

This one feels a bit redundant; it’s going to be supported by later portions of the code, particularly training and internal audits. There’s no specific action here other than showing evidence of implementing and enforcing food safety practices. We can move on.

2.1.2.3 The senior site management shall ensure adequate resources are available to achieve food safety objectives and support the development, implementation, maintenance, and ongoing improvement of the SQF System.

Again, this portion of the code doesn’t require a specific form or policy to be in place. It’s going to be audited throughout the entire system. If things are out of repair, not being improved, or otherwise not happening due to time or cost constraints, it becomes evidence that 2.1.2.3 has not been supported.

2.1.2.4 Senior site management shall designate an SQF practitioner for each site with responsibility and authority to:

i. Oversee the development, implementation, review, and maintenance of the SQF System, including food safety fundamentals outlined in 2.4.2, and the food safety plan outlined in 2.4.3.

ii. Take appropriate action to ensure the integrity of the SQF system; and

iii. Communicate to relevant personnel all information essential to ensure the effective implementation and maintenance of the SQF System.

Here we are, the SQF practitioner. You must designate, either on your organization chart or in a job description, the individual(s) who is(are) ultimately responsible for the effective implementation of the system. This can be the CEO, a dedicated quality role, or anyone that makes sense for the company size and structure, but they need in their job description both the assigned role of SQF practitioner, and the authority to do it effectively.

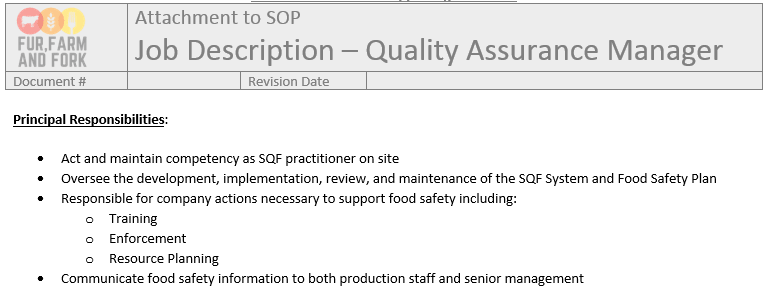

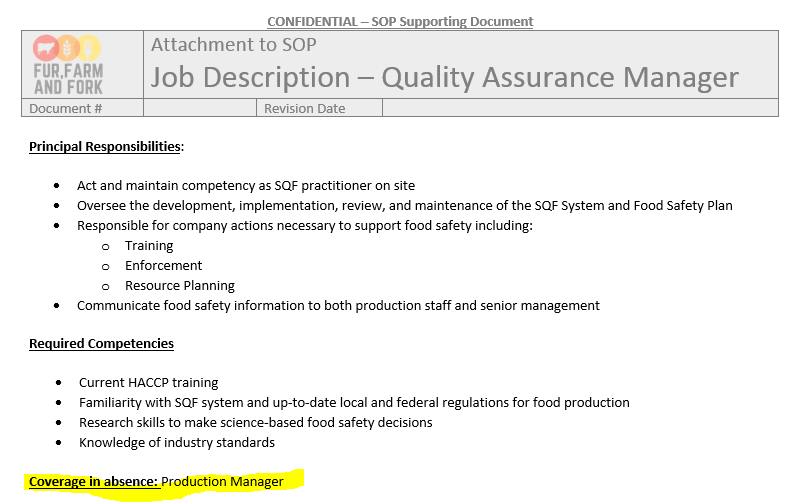

Here’s an example of how to integrate assignment of a practitioner into a job description, my preferred method since these descriptions need to be made regardless:

Other ways to designate are to include the designee in the management commitment statement, or identify them on the organization chart similarly to how we selected individuals responsible for food safety. The point is that a specified individual was chosen, they have sufficient authority, and other employees know who they are.

2.1.2.5 The SQF practitioner shall:

i. Be employed by the site as a company employee on a full-time basis;

ii. Hold a position of responsibility in relation to the management of the site’s SQF System;

iii. Have completed a HACCP training course;

iv. Be competent to implement and maintain HACCP based food safety plans; and

v. Have an understanding of the SQF Food Safety Code and the requirements to implement and maintain SQF System relevant to the site’s scope of certification.

Here we’ve reiterated the basic requirements of a practitioner, but also provided some additional detail on what needs to be on file. As above, first and foremost the SQF Practitioner needs to be a paid employee with sufficient authority to get things done in the production areas. No interns, no offsite sales representatives, no lawyers on retainer.

A HACCP training course is required (specifically CODEX HACCP, not an FDA juice HACCP, seafood HACCP, and NOT Preventive Controls Qualified Individuals classes, though if you’re in the US those will be required for regulatory compliance reasons). Note that no where in the code or guidance does SQF use the term “certified”.

A personal pet peeve of mine is inappropriate use of the word certified. Certified means that some sort of organization determined that you met their standards and said you can call yourself certified. Therefore, if you want to take my class about HACCP under Fur, Farm, and Fork’s standards, I can call you “certified” under the FF&F standard for HACCP.

SQF makes no requirements what “standard” of HACCP training is needed, other than training needs to exist on paper. Therefore, as an example you could take IFSQN’s compact, inexpensive, 4 hour class. By doing so, you’ve met the written requirements of the code and you even have a certificate to show an auditor when they ask. Done and done.

Anything demanded other than “HACCP training was provided and documented” is not code but auditor preference. However, when preference becomes a fight it may not be worth starting to argue early in the audit. Besides, additional training isn’t a bad thing. One industry gold standard for HACCP training is a workshop type HACCP class that incorporates at least 16 hours of classroom time, and is accredited by an organization with some recognized weight such as the international HACCP alliance.

Many certifying bodies sell HACCP training/certification services, feel free to take advantage, but remember that the code does not require anyone’s specific training (despite what salespeople say). Of course, you won’t be able to support the efficacy of the training you received if your HACCP plan isn’t up to snuff, which is why the code follows up the training requirement with “Be competent to implement and maintain HACCP based food safety plans”.

The evidence that the training was effective will be in the plan. If the plan does not include monitoring and verification of critical control points, and you have no idea that it’s incomplete, that’s nonconformance with 2.1.2.5. You demonstrated that the practitioner does not have the required competency to make a functional plan, and it may have been because they didn’t have effective HACCP training.

Finally, SQF basically says that the SQF practitioner needs to know the code well enough to implement it. Again, this can be accomplished through either training, experience, consultant help, or personal study, but it will be evaluated during the audit based on how many times you say “I didn’t know that was in the code”. So, do whatever is necessary to know this stuff; If you’re reading this blog series, you’re on the right track 😉.

2.1.2.6 Senior site management shall ensure the training needs of the site are resourced, implemented, and meet the requirements outlined in system elements, 2.9, and that site personnel have met the required competencies to carry out those functions affecting the legality and safety of food products.

Again, this is reiterating that the training requirements we’ll go into detail on later have evidence that they’re effective, no specific action here other than showing that the auditor is looking for competence, not just paperwork exercises.

2.1.2.7 Senior site management shall ensure that all staff are informed of their food safety and regulatory responsibilities, are aware of their role in meeting the requirements of the SQF food safety code, and are informed of their responsibility to report food safety problems to personnel with authority to initiate action.

The first portion of this is again going to be based on employee interview, knowledge, and demonstrated competency during the audit. However, hidden in this clause is an obvious but not always written requirement that “employees are informed of their responsibility to report food safety problems”.

This can be embedded in the management commitment statements, an employee “day one” SOP, or other training tool. But an employee on the floor needs to be able to say they know that they need to report when something has gone wrong and that they have the support and authority to do so.

Keeping it simple: this reporting method can be as simple as “report to supervisor as soon as condition is observed”. But this reporting method needs to be actually written down and documented in a trained policy or procedure.

The culture change necessary to make consistent reporting a reality is hard, but the demonstrated training portion is easy. When training employees on the basics on day one like when to wash hands, PPE, etc., include a responsibility to report food safety problems.

2.1.2.8 Job descriptions for those responsible for food safety shall be documented and include provision to cover for the absence of key personnel.

Everyone identified as personnel responsible for food safety in the org chart needs a job description, and that job description specifically needs to call out that they have a responsibility to food safety. But, there’s no requirements about formatting, content, etc. except one.

In general, when approaching required paperwork for SQF, if they’re mandatory, make them useful to your business. Work with the HR team to generate job descriptions that clarify responsibilities and competencies for employees in key roles and use it for performance accountability. I’ve got a template below of a bare bones description that I’ve found useful.

There is that one specific requirement for “provision to cover for the absence of key personnel.” Key here is that SQF wants to make sure that food safety isn’t dependent on the practitioner being on vacation, but that the company maintains both standards and tools (e.g. can’t stop verifying thermometers just because the lab tech is out) rather than just placing it all contingent on one person’s presence.

Why I don’t like this provision is that it requires it to be written into the job descriptions. Job descriptions aren’t usually very “live” documents, and making (SQF) certified suppliers document this specific provision in a specific place is burdensome. In my humble opinion, this should be audited similar to other responsibility provisions in that the proof will be in actual demonstration of the coverage. Instead it becomes a checkbox on the audit list, making this is a very common non-conformance when suppliers don’t follow the code and place it exactly where it’s supposed to be in the paperwork.

So, the most audit-proof way to meet this requirement I’ve found is to take the code very literally, and add a “coverage in absence” line to your job descriptions.

2.1.2.9 Senior site management shall establish processes to improve the effectiveness of the SQF System to demonstrate continuous improvement.

Once again, this will be demonstrated through internal audit and management review systems to be discussed further.

2.1.2.10 Senior site management shall ensure the integrity and continued operation of the food safety system in the event of organizational or personnel changes within the company or associated facilities.

Basically, if an SQF practitioner gets laid off or goes on leave, is everything going to fall apart? This is another one that will be demonstrated via observation during the audit. If things have fallen through the cracks that are normally done (supplier review, internal auditing, reporting, verification tasks) and the excuse is that there was an organizational change, that’s a problem under this clause. Doesn’t matter if you just moved into a new building or got a new boss, the standards are supposed to continue to be met.

2.1.2.11 Senior site management shall designate defined blackout periods that prevent unannounced re-certification audits from occurring out of season or when the site is not operating for legitimate business reasons. The list of blackout dates and their justification shall be submitted to the certification body a minimum of one (1) month before the sixty (60) day re-certification window for the agreed up on unannounced audit.

Basically, SQF has no interest in auditing a seasonal facility that is not producing anything that month. Alternatively, if the facility only operates Mon-Thus. Then SQF doesn’t want to pop in unannounced on a Friday and find nobody there. On years with unannounced audits, communicate with the certifying body regarding what days are actually going to be worth visiting.

As a bonus, you can also try to specify blackouts like planned vacations for key personnel or your SQF practitioner(s). While the SQF system needs to be maintained when those people are out, Audits are a different situation that does not require everyday coverage. There’s an expectation that the system is maintained, but certain folks will be able to explain the system in its entirety during an audit that others will not. I’ve had good luck with CB’s when blacking these out, provided it doesn’t defeat the purpose of an unannounced audit by blocking out the majority of the window.

How will this be audited?

SQF guidance tells auditors to be patient when gauging compliance with 2.1.2, as it’s the proof that the system isn’t just a pile of SOP’s and verification records. It can take time to tease that out of a company that knows how to “pencil whip” an audit.

There are some items that will be reviewed at the desk: job descriptions, HACCP training proof, maybe the resume of the SQF practitioner, and organization charts. But the majority of this clause is just saying “we made you do all of this stuff…are you actually doing it even when it’s hard?”

- A leaky roof or broken floor that’s been there for 2 years of audits is evidence that the business has not been allocating sufficient resources to maintenance.

- A team that has no idea that they are supposed to be monitoring a critical control point to keep the food safe is not one that was actually trained well.

- A vacant microbiologist position combined with raw materials no longer being tested on site is evidence that the company has not provided for coverage and the system fails when individuals are absent.

- A HACCP plan that doesn’t have a process flow for a product launched last month is not being reviewed or updated enough to support food safety in the plant.

- Not having FSMA requirements in place is evidence that staff are not keeping up with new regulatory requirements and implementing them.

- A sanitation schedule that says “clean once a day” but records show days are skipped when we “get busy” or too many people call in sick is evidence that the SQF practitioner does not have sufficient authority to implement the plan.

- Microbiologists were no longer using the paddle blender because they didn’t like waiting for it to finish, signing off one procedure and doing another is evidence of ineffective training and lack of competence for the role.

- An SQF practitioner that is expected to maintain the system while also performing all front desk, office management, freight scheduling, product testing, production scheduling, and outside sales support; didn’t update the old SOP’s potentially because they have not been allocated the time to do the job properly.

In the plant, while inspecting the line and problems are noted, if you are already aware of them with a plan in place to fix, sharing it demonstrates planned improvement and resource allocation, even if occasionally an auditor with no company responsibility may disagree with the timeline.

In a real business environment, not everything can be fixed right away. But you can demonstrate management responsibility by providing a plan, with deadlines, and how you will mitigate risk until the fix happens. Continuous improvement is not immediate improvement, show what you’ve fixed so far to demonstrate your commitment, and you will give the auditor confidence that the things they see will be fixed according to plan as well.

2.1.2 takes management commitment and calls the bluff. It starts with creating a system and providing resources so that the code can be upheld no matter what, and ends with a competent practitioner that keeps it on track and makes sure the company is never “surprised” by gaps in their system. SQF practitioners should demonstrate command of their own system and facility, with its weaknesses already known and highlighted for future improvements.

Author Biography:

Austin Bouck is a food safety consultant and manufacturing supervisor in Oregon, USA. You can find more food safety resources and discussion on his website, Fur, Farm, and Fork, as well as contact information for consulting services.

5 Comments

Austin -- How do you like to think about creating a system?

I have a few ideas that often pass through my head:

A system in passes - much like a 3d printer, starting with a few basic items and then repeating and refining on top of those after laying down a foundation.

End to end - Front to back building a system sort of like a checklist.

Inside out - Much like in passes, starting with a core and adding around it more, additional detail.

Big to small - Much like writing - starting with generalisms to focus down to the topic at hand, with the creation of the end product fulfilling the broader requirements.

Realize this is a bit of a qualitative question more than a practical one, but I'd be curious what you've found as made the most sense when there are many sets of requirements to fulfill and the core "should" fit all the fine points when done correctly.

Definitely Inside out. As far as food safety programs go, always start with the food safety plan. The rest of the programs are to make sure that risk management system is supported.

So grateful you are breaking this down, and making it easier to understand. I look forward to every episode! Thank You

Thanks for the article, Austin! Good work.

Matthew

Thank you for the article!

Is it ok for the primary SQF practitioner to report to a corporate person, like corporate QA manager, instead of the senior management at the site, like the factory manager?

Thank you!