3 votes

3 votes

Meeting the new requirements of SQF 8.0: 2.7.2 Food Fraud

Having been through one of the first round of SQF 8.0 audits, I wanted to help other folks who may be sweating some of the new clauses. So, here’s an example of the approach I took to get me through my audit in February that may help other SQF practitioners.

The requirements in the SQF code 8.0 module 2:

2.4.4.5 The site's food fraud vulnerability assessment (refer to 2.7.2.1) shall include the site's susceptibility to raw material or ingredient substitution, mislabeling, dilution and counterfeiting which may adversely impact food safety.

2.4.4.6 The food fraud mitigation plan (refer to 2.7.2.2) shall include methods by which the identified food safety vulnerabilities from ingredients and materials shall be controlled.

2.7.2.1 The methods, responsibility and criteria for identifying the site's vulnerability to food fraud shall be documented, implemented and maintained. The food fraud vulnerability assessment shall include the site's susceptibility to product substitution, mislabeling, dilution, counterfeiting or stolen goods which may adversely impact food safety.

2.7.2.2 A food fraud mitigation plan shall be developed and implemented which specifies the methods by which the identified food fraud vulnerabilities shall be controlled.

2.7.2.3 The food fraud vulnerability assessment and mitigation plan shall be reviewed and verified at least annually.

2.7.2.4 Records of reviews of the food fraud vulnerability assessment and mitigation plan shall be maintained.

The associated guidance material:

What does it mean?

In July 2014, GFSI published a discussion paper “GFSI position on Mitigating the public health risk of food fraud,” in which it states “The GFSI Board recognizes that the driver of a food fraud incident might be economic gain, but if a public health threat arises from the effects of an adulterated product, this will lead to a food safety incident.”

Food fraud is often described as EMA, economically motivated adulteration. However, it is more than that. As well as adulteration, food fraud includes substitution, dilution, addition, misrepresentation or tampering of food ingredients or food products. It is in fact illegal deception for economic gain.

The economic risks of food fraud to the industry are apparent. It is estimated that fraud costs the global food industry between $US40bn -$US50bn every year (Australian Food News, 11th July 2017). However, the public health impacts are less so. In many cases, the health impact of food fraud is not known until after the fact, when consumers become sick and the adulterant is detected.

GFSI now requires that a food fraud vulnerability assessment and mitigation plan to be incorporated into the food safety management systems in all GFSI benchmarked schemes. SQF in edition 8 now requires food fraud to be considered for the site (2.7.2), and for incoming materials and ingredients (2.4.4.5, 2.4.4.6).

What do I have to do?

Although this element is not mandatory, it is a key GFSI requirement and can only be exempted on receipt by the Certification Body (CB) of a written request from the site justifying exemption. If the justification is accepted by the CB, the element can be exempted. If not, and the site has not completed a vulnerability assessment and mitigation plan, then the CB is required to raise a major non-conformance against 2.7.2.

For many sites, food fraud is a new consideration and the hardest part is getting started. What is a vulnerability assessment? What is a mitigation strategy?

The food fraud strategy is similar to the HACCP methodology sites are familiar with. In general terms, it is:

1. Identify the risks (vulnerabilities)

2. Determine corrective and preventative actions (mitigation strategies)

3. Review and verify

4. Maintain records

The food fraud requirements talk about ‘vulnerabilities’ rather than ‘risk’. A risk (ISO 31000 Risk Management) is something that has occurred frequently before, will occur again, and there is enough data to conduct a statistical assessment. Vulnerability is more a condition that could lead to an incident (Dr John Spink, MSU). GFSI considers an “incident” to be a “consumer health risk if not addressed.”

‘Vulnerabilities’ need to be identified in incoming materials and ingredients, and within the site. Not all materials and ingredients are subject to risk, and the highest risks may be from minor or infrequent ingredients that originate from sensitive geopolitical areas, or suppliers with poor past histories. Ingredients can be prioritised based on perceived risk.

Within the site, vulnerabilities may include the potential for intentional or accidental substitution, dilution, or adulteration. The question that needs to be asked is “who benefits financially from internal food fraud?”

Mitigation strategies will be developed based on the identified vulnerabilities.

Although SQF requires that the food fraud vulnerability assessment and mitigation plan to be reviewed and verified at least annually, the site should be constantly aware of their supplier history and changes in the supply chain that could impact the vulnerabilities.

SQFI recommends that suppliers initiating their food fraud strategies seek assistance from one of the many resources that are available on-line. Although SQFI lists these resources, we take no responsibility for the information they provide or the outcomes of the assistance they offer.

SQFI partners with the Food Fraud Initiative at Michigan State University (MSU) http://foodfraud.msu.edu. This group offers free on -line training for sites and auditors on food fraud called Massive Open On-line Courses or MOOCs.

Other resources that could be considered include the PwC food fraud vulnerability assessment, and the USP Food Fraud Database.

Auditing Guidance

As with suppliers, food fraud is also relatively new to auditors, and SQFI recommends that all SQF auditors seek training in food fraud strategies through the resources outlined above, or through their internal CB training.

The auditor must avoid pre-determining site’s food fraud vulnerabilities or making a quick decision on 2.7.2 Food Fraud. Food fraud is a new and inexact science, and there is no prescribed methodology for determining vulnerabilities or their mitigating actions. It is based on the information that the site has available at the time.

The auditor will seek evidence of compliance to this requirement by review of documents and records, and interview. Evidence may include:

- There is awareness within senior management of the need for a food fraud vulnerability assessment and mitigation strategies.

- There is a current, documented vulnerability assessment in place that identifies key ingredient vulnerabilities including justification for their inclusion. The methodology for selecting the key ingredient vulnerabilities shall be available.

- The vulnerability assessment shall include an evaluation of the site vulnerabilities including from staff, contractors, and other associates.

- There are documented mitigation (ie prevention) strategies in place for all identified vulnerabilities, which identify what is to be done and who is responsible.

- The mitigation strategies are active, and are being reviewed for effectiveness.

- The vulnerabilities and mitigation strategies are reviewed at least annually.

- There are records available of review of the food fraud program.

1. A vulnerability assessment must be conducted that includes an assessment of our susceptibility to the following types of fraud which may affect food safety (or quality if you’re under the quality code)

1. Substitution

2. Mislabeling

3. Dilution

4. Counterfeiting

5. Stolen goods

2. A mitigation plan shall include methods we use to control the identified vulnerabilities we identified in the vulnerability assessment that apply to us.

3. A policy/SOP needs to state that we will conduct this vulnerability assessment at some interval and support it.

4. We need evidence that the mitigation plan was implemented

5. The plan gets reviewed annually, and some sort of verification takes place

6. There need to be records of some kind

7. They specifically state that it is similar to the HACCP methodology, so I should basically incorporate it into my HACCP plan anyway

What I did

I created a new “top tier” SOP titled “Food Fraud Vulnerability Assessment”. This ensured that I had a record of management review annually (signatures), it was signed off by the CEO (knowledge), and outlined “methods and responsibilities”.

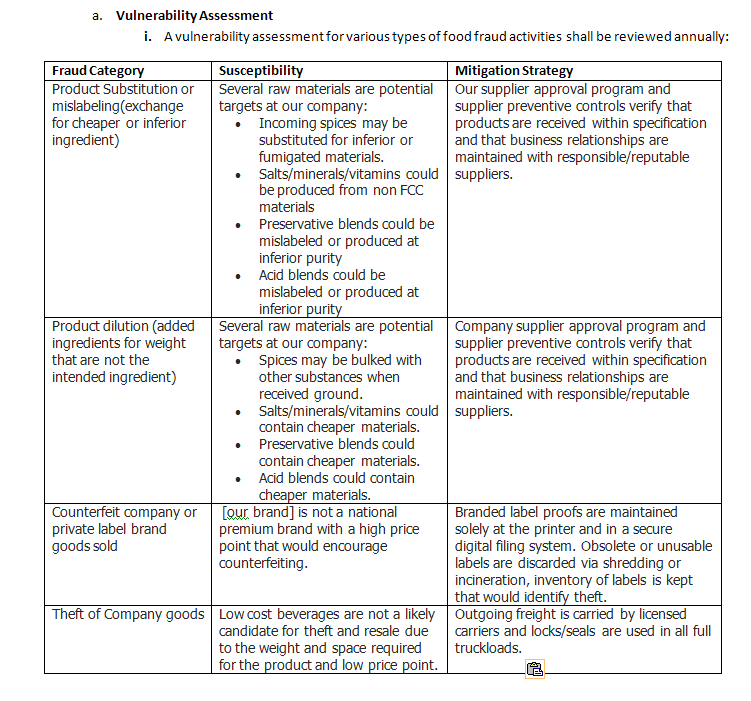

I then completed this table for my vulnerability assessment and mitigation strategy, note that YOUR COMPANY’S identified susceptibility and mitigation strategies will be different than the examples below, but the fraud categories are all those that were specifically identified in the SQF Code (note, susceptibility and mitigation strategies below are just examples, but are very similar to that which was audited by NSF at my facility):

This fulfilled my requirements to perform an assessment of vulnerabilities to the types of fraud identified in the SQF code, and identified mitigation strategies to control them as appropriate.

The procedure section of the SOP indicated that individual ingredient assessments would be carried out through our food safety plan, supplier approval procedure, and ingredient specification maintenance. Label control was outlined in our labeling SOP, and loading/shipping controls were outlined in that SOP. This tied all the documentation/records/evidence from all our prerequisite programs and HACCP documentation together.

Finally, in addition to “physical, chemical, biological, radiological, allergen” hazard categories included in my hazard analysis, I included “food fraud” as a category anytime it was a “receipt of material” or a specific ingredient, and identified if any FOOD SAFETY hazard required additional controls beyond those included in the vulnerability assessment to ensure that no safety hazard introduced via fraud was at an unacceptable level of control.

As always, all auditors are different, and each SQF audit is conducted independently where non-conformities may be noted in future audits even if the material does not change. However, this approach above was considered solid evidence of compliance in our audit conducted February 2018. Hopefully this helps some other folks out who don’t know where to start.

Author Biography

Austin Bouck is a quality assurance manager at a regional beverage company in Oregon, USA. When not at work solving technical quality challenges, he continues to ponder food safety issues on his blog, Fur, Farm, and Fork, which helps him stay sharp and share his knowledge with other professionals and the public.

Thanks for yr efforts to assist would-be VA-ers. I assume the audit was for the Manufacturing Code.

A few comments -

(1) I am curious how the auditors assessed yr Program/Data for Safety vs Non-Safety aspects ?. Offhand I cannot recall ever seeing such a distinction attempted in the current published Literature due the normal all-inclusivity interpretation of "Food Fraud".?

(2) To my eyes, the word "Safety" does not occur anywhere in the elegant table above.

(3) One wonders whether so much effort to include so many "statistically-unlikely-to-be-safety-related" defects in a Risk-Based, Food Safety System is justified on the Principle of "catching" unintended, unpredictable, disasters like melamine. Difficult.

(4) afai could determine (not my area), FDA (FSMA) is not requiring evaluation of external (to the manufacturing site), Food Quality hazards (SQF terminology) which GFSI/BRC/SQF would regard as within its definition of Food Fraud ?.