- Home

- Sponsors

- Forums

- Members ˅

- Resources ˅

- Files

- FAQ ˅

- Jobs

-

Webinars ˅

- Upcoming Food Safety Fridays

- Upcoming Hot Topics from Sponsors

- Recorded Food Safety Fridays

- Recorded Food Safety Essentials

- Recorded Hot Topics from Sponsors

- Food Safety Live 2013

- Food Safety Live 2014

- Food Safety Live 2015

- Food Safety Live 2016

- Food Safety Live 2017

- Food Safety Live 2018

- Food Safety Live 2019

- Food Safety Live 2020

- Food Safety Live 2021

- Training ˅

- Links

- Store ˅

- More

Advertisement

Featured Implementation Packages

-

IFSQN FSSC Development Program Food Safety Management System Implementation Package - Version 1

The IFSQN FSSC Development Program Food Safety Management System Implementation... more

-

FSSC 22000 Food Safety Management System for Food Service - Version 5.1

This is a tailor-made food safety management system implementation package for C... more

SQF from Scratch: 2.1.5 Crisis Management Planning

Apr 14 2020 05:10 PM | Simon

SQF 2.1.5 Crisis Management Planning

2.1.5 Crisis Management Planning

Well…this sure got relevant in the past few months.

SQF understands that businesses aren’t just going to sign yearbooks and close the doors if a disaster happens. In the most philanthropic mindset, food businesses play an important infrastructure role, but if we’re honest, the common motivation is that owners and employees care about the business they have. If there’s still a way to operate, we won’t be ready to just call it quits when faced with a disaster.

“If the sour cream line still works we can make it through this, let’s start digging.”

With customer loyalty, cashflow needs, and employee job security at stake, companies will try and find a way to get products out the door as quickly as possible. What SQF wants to see is that they aren’t just going to throw food safety out the window due to “extenuating circumstances”, even if they’re legitimate.

HACCP plans include corrective actions so that we determine the right course of action before knowing what the cost will be. Similarly, a crisis management plan made in “peacetime” will ensure we had the time and capacity to commit to sound food safety decisions before the sewage hit the fan.

The code:

2.1.5 Crisis Management Planning

2.1.5.1 A crisis management plan that is based on the understanding of known potential dangers (e.g., flood, drought, fire, tsunami, or other severe weather or regional events such as warfare or civil unrest) that can impact the site’s ability to deliver safe food, shall be documented by senior management outlining the methods and responsibility the site shall implement to cope with such a business crisis.

2.1.5.2 The crisis management plan shall include as a minimum:

i. A senior manager responsible for decision making, oversight and initiating actions arising from a crisis management incident;

ii. The nomination and training of a crisis management team;

iii. The controls implemented to ensure a response does not compromise product safety;

iv. The measures to isolate and identify product affected by a response to a crisis;

v.The measures taken to verify the acceptability of food prior to release;

vi. The preparation and maintenance of a current crisis alert contact list, including supply chain customers;

vii. Sources of legal and expert advice; and

viii. The responsibility for internal communications and communicating with authorities, external organizations and media.

2.1.5.3 The crisis management plan shall be reviewed, tested and verified at least annually.

2.1.5.4 Records of reviews of the crisis management plan shall be maintained.

What’s the point? How is this making our product safer?

This element can feel out of place if we get swept up with focusing on the business and personal safety aspects of the crisis. SQF didn’t help with previous language in the code which used to reference “business continuity”, which read as business oriented versus food safety.

The current language of the code does a much better job of making clear that the point of this element is to make sure the site doesn’t just start pitching out unsafe product in order to keep the business alive. We know from previous outbreaks and litigation that, when faced with significant financial impacts, companies will feel pressure to make poor food safety decisions.

We see these events and start to think, if a company is willing to release unsafe food just to avoid losing a single customer…what would they be willing to release to keep the business from closing?

In the same way a starving person will eat from the trash, a business crippled by natural disaster will have immense pressure to sell anything, and its personnel won’t feel like they have the time or resources to find a better solution.

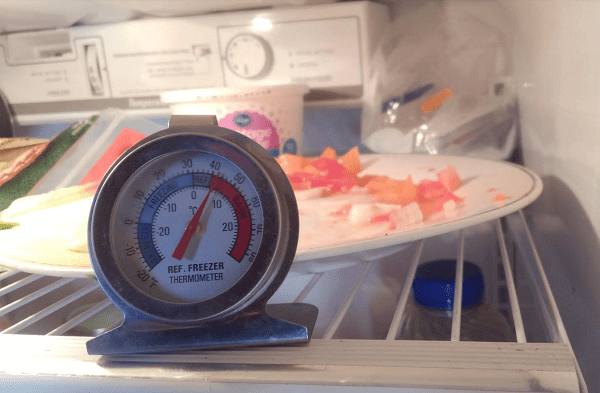

Imagine being a local meat distributor, and a massive blackout hits the city one week before thanksgiving. The 6 team members on site are staring at a warehouse holding 3000 turkeys that are now warming up. They have 4 hours to figure out a solution that maintains all of their various requirements….or play it by ear and hope the power goes back on. I mean, are we really prepared to toss everything on inventory the week before a holiday just because it got a little warmer than it should? It’s not like there was a sewage leak all over it and the turkeys will be cooked for hours!

Even if the best solution was to get a block of ice for every single turkey, who sells that? Do they have the capacity? How will it be transported? Figuring out the logistics will also take time, maybe so much time that the company will be in the same situation anyway, less the effort.

Rather than wait until the moment the building loses power, this is a reasonably foreseeable event that SQF states suppliers should already have planned for. So that when through no fault of their own they face a crisis, there is a plan in place that puts food safety as a priority.

What am I being asked to do?

Making the Plan

The practitioner needs to develop a policy/procedure document that includes all of the elements outlined in the code. Some of these feel silly, like identifying a “senior decision maker” (isn’t that why we have an organization chart and job descriptions already?), and some of them can be very burdensome for the QA team if we aren’t taking steps to keep the documentation lean. Let’s look at how we can include these point by point.

2.1.5.1 A crisis management plan that is based on the understanding of known potential dangers (e.g., flood, drought, fire, tsunami, or other severe weather or regional events such as warfare or civil unrest) that can impact the site’s ability to deliver safe food, shall be documented by senior management outlining the methods and responsibility the site shall implement to cope with such a business crisis.

The plan needs to give consideration to specific crisis that are reasonably foreseeable. Frankly, outside of some site or region-specific natural disasters (such as tsunami, tornado, ammonia leak), most of these will be the same for any company. I recommend identifying the following at minimum:

• Fire

• Structural failure from weather, flood, sabotage, accident.

• Prolonged Power Loss

• Food-based or biological terror attack

• Epidemic

• Civil Unrest or Domestic Terrorism

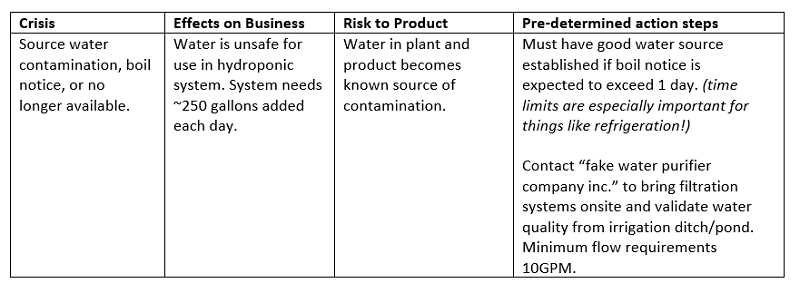

• Source water contamination, boil notice, or no longer available

These are all reasonably foreseeable in any location, and do a decent job of providing some categorical planning (e.g. prolonged power loss could be a secondary crisis to any of the above) to allow for the unforeseen stuff.

i. A senior manager responsible for decision making, oversight and initiating actions arising from a crisis management incident;

ii. The nomination and training of a crisis management team;

…

viii. The responsibility for internal communications and communicating with authorities, external organizations and media.

These sections of the code are more relevant to larger companies, which may have rotating “task forces” for these things like the HACCP Team, Recall Team, and Crisis team. In a small company, the final decision maker in all of these situations is generally going to be the lead person at the site (based on the organizational chart). The SQF practitioner is still going to be on all of the teams.

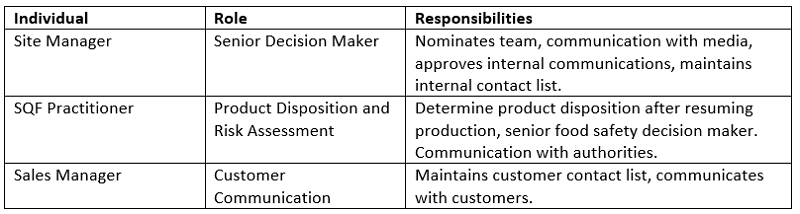

As with all employee lists in documentation, I encourage the use of job descriptions rather than names so that they remain relevant with regular turnover. For this list, we can outline the responsibilities required in the code as well and knock out a few other requirements. For example:

Crisis Management Team

In the event any of the above individuals is incapacitated or unavailable, their successor in the Job description or organizational chart will be trained on this procedure to stand in that role temporarily.

SQF does not specify any particular training this team requires, so make sure they are trained on the procedure itself or that they participated in creating/modifying the plan (make sure to document).

iii. The controls implemented to ensure a response does not compromise product safety;

This is why the plan exists. Looking at the “foreseeable events” we identified above, think about the last one, “Source water contamination, boil notice, or no longer available”. If I was farming hydroponically in greenhouses and happened to be using municipal water, I may be immediately willing to use nearby irrigation sources in the event of a boil notice. However, without having ever investigated that water or ensured it didn’t present any new hazards in my food safety plan, that rapid response could compromise food safety.

If, however, I had determined that the water source was acceptable with appropriate filtration in place, I could have those details outlined in my plan! For everything identified as reasonably foreseeable, determine what hazards are created, what actions would be needed to address them, and fleece them out to make sure there is a feasible plan in place in the event of a crisis.

“Before resuming production, conduct a hazard analysis for any response/recovery/repair that resulted in a process flow change and/or any new hazards that have been introduced to the facility due to the crisis to ensure safety of product.”

iv. The measures to isolate and identify product affected by a response to a crisis;

v.The measures taken to verify the acceptability of food prior to release;

To keep this document under control, we need to use our golden rule and rely on systems we already put in place. Therefore, this document should reference the existing recall plan, corrective action procedures, product hold procedures, product release procedures, and hazard analysis, rather than rewrite them all.

There is absolutely NO REASON to create a special, duplicated, or different corrective action procedure here. The quality team deals with non-conforming products and hazards every day, they should be approached using the same methods and documentation already in place.

Make sure these references are clear, obvious, and appropriately notated so that procedures only need to be updated in one location whenever possible! It can be helpful to include a general statement regarding product disposition in the policy section prior to mentioning it in the step-by-step procedure (should be the first thing that happens after we made sure everyone is safe and we can all communicate). The reference can look something like this:

“Product Evaluation and Disposition

Any product either already produced or in production in the event of a crisis shall be identified, isolated, and evaluated for disposition using Corrective and Preventative action investigation procedures and the food safety plan. Product for which safety cannot be reasonably assured shall be isolated and recall procedures initiated as necessary.

Product produced or released after a crisis response has been initiated shall be evaluated for disposition using corrective and preventative action investigation procedures. Product for which safety cannot be reasonably assured shall be isolated and recall procedures initiated as necessary. Should crisis response result in a process flow change, a new hazard analysis will be performed to evaluate the controls necessary to maintain product safety.”

vi. The preparation and maintenance of a current crisis alert contact list, including supply chain customers

vii. Sources of legal and expert advice; and

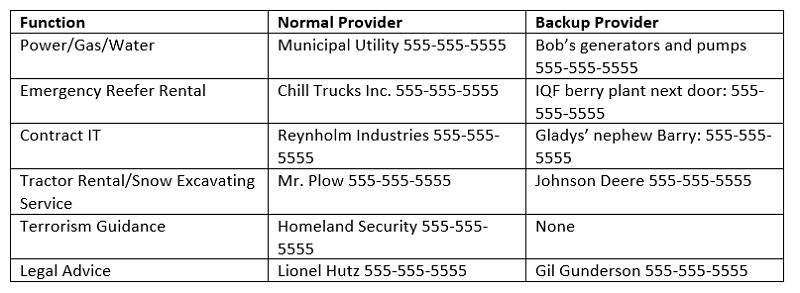

This is a tricky one, again, the goal is to avoid duplicating anything in this plan that’s going to be reviewed annually anyway, but we really should make sure we know who to call when disaster strikes (the recall plan has similar needs).

These lists may be in different locations, so make sure the plan explains how to access them as well as the employee/department responsible for maintaining them.

For customers, we can use the contact lists the sales and customer service teams maintain. However, these lists to be producible during an audit. Grabbing the sales manager’s cell phone and explaining that “Dave J.” is the contact for a major grocery chain is not going to fly. This is a good one to aggressively test annually, especially if computer systems or key personnel are unavailable during the crisis. Where are the phone numbers/email addresses, can they be produced, are we pretty sure they all still work, and what will we do if they don’t?

There needs to be similar contact lists for company staff, but those tend to be maintained by HR or office administration.

The final contacts that need to be available are providers of essential services. This is a really helpful component of the plan, and one that’s very testable. Identify “essential functions” of the business and the appropriate contacts. Common ones are utilities, communications (phone and internet), government resources (police, FBI, USDA/FDA), insurance providers, legal advisors (this is in the code, put someone down, insurers usually have recommendations), and distribution partners; additional helpful contacts would be contract service providers for things like emergency refrigeration (maybe bring diesel refrigerated trucks on site), contractors for emergency building repair, and equipment maintenance.

Here's an example of some essential function providers:

2.1.5.3 The crisis management plan shall be reviewed, tested and verified at least annually.

2.1.5.4 Records of reviews of the crisis management plan shall be maintained.

Just like with other major elements, it’s often the plan review that trips folks up. Unlike other policies that just need an “annual review” (a.k.a. read, modify, sign), this plan needs to be exercised using a mock scenario like the recall or food defense plans.

Not going to lie. These are awkward. There are simple and helpful portions of the test, like making sure that all of the contacts are still current/relevant and the planned responses are still feasible. Detail those checks in the test documentation as it provides evidence a thorough review was conducted.

However, auditors want a test with a mock incident. This entails coming up with a scenario, going through the procedure, using the contact lists, and basically conducting a roleplaying game of an incident. It can be fun…or it can feel silly. Depends on the group.

My recommendation, pick a disaster that is very likely (no reason to do something crazy like volcanic eruption or pandemic…wait) and talk through the plan with the team. See if everything makes sense and do a hazard analysis on any changes that would need to take place. Structural damage is a good candidate. It’s easy to think about the existing facility and how to get up and running again while shielding product from the elements, having to evaluate the disposition of items that were in the building at the time, etc.

(bonus, you can also highlight some needed maintenance and use it to demonstrate what the impact will be if that structure fails)

Document the review by writing down a hazard analysis formatted like the food safety plan, the team’s ideas, and what resources would be need to be available (e.g. if the phones don’t work how to we contact our senior decision maker?). Use the crisis procedure as a guide and write down the team’s mock responses to each step.

How will this be audited?

This section of the code has been revised a lot, and will have various opinions attached to how it should look, so be prepared to explain the documentation and rationale at length. Once the specific elements of the code are checked off, the meat of the auditing fall most heavily under the management commitment and review umbrella. Auditors want to see that the team took it seriously and thought about how they will make sure food safety is maintained in a crisis, not just when it’s easy.

Auditor red flags will go up if presented a plan that only has vague, generic crises like floods or fire, and that the tests are similarly non-specific (what part of the building was the fire in?). Other red flags will be any statements, both in the plan and spoken during the audit, that claim “we just wouldn’t produce” or “we would shut down”.

Those aren’t appropriate responses because everyone knows better! If every crisis was so catastrophic that the business was immediately destroyed no one would need this plan. “We wouldn’t run” plans imply that the practitioner threw together a document to meet the requirement and didn’t use it as a tool for food safety or hazard analysis.

The testing document needs to reflect a real consideration of an event, not just reading the procedure and signing. It’s not a hard and fast rule, but testing documentation that doesn’t include any plan revisions, corrective actions, or updates of any kind is going to be assumed to have been on paper only. If indeed the team found nothing to update or improve about the plan, document the crew’s thoughts and that conclusion, leaving no doubt that the test was thorough.

The more the test documentation demonstrates that a group came together to fully consider a crisis, the better. While it can be done with a checklist (and at minimum the SQF elements should be reviewed), it will read much better as a narrative during the audit.

If an all-star team is 5 years in and stuck in a rut on a well-prepared plan, throw additional wrenches in the works! Make sure that flood takes out one of the raw material suppliers so that the team needs to find and approve a backup. Or select disasters that provide no government guidance (e.g. structural failures that affect specific areas of the building or transportation/logistics concerns from a strike). Remember that disasters that don’t happen INSIDE the facility will still affect it.

2.1.5 is an extension of the food safety plan, an opportunity to take hazard analysis skills and make sure they can still be applied when things get crazy. Putting time and thought into these scenarios is a demonstration of management commitment; that the SQF system is not just “fair weather” guidance that goes out the window when times get tough, but that we’ve incorporated them into our company’s priorities and that they will remain so, even when everything is at risk.

Right now, around the world, food manufacturers are learning to work within the new normal, a set of hazard considerations that they’ve probably never thought of that are affecting every single part of their business model.

But here and there, there were trained SQF suppliers that were able to take a deep breath and say, “okay then, let’s execute the plan and get these products moving.”

Author Biography:

Austin Bouck is a food safety consultant and manufacturing supervisor in Oregon, USA. You can find more food safety resources and discussion on his website, Fur, Farm, and Fork, as well as contact information for consulting services.

1 Comments

Austin - thanks so much for this excellent series of articles. We are a very small start-up gearing up for SQF certification and your in-depth review and practical application of the individual SQF standards is really helping us to better understand them and to determine what actions make the most sense for us. Thanks again for providing this valuable resource on our journey to certification!!