- Home

- Sponsors

- Forums

- Members ˅

- Resources ˅

- Files

- FAQ ˅

- Jobs

-

Webinars ˅

- Upcoming Food Safety Fridays

- Upcoming Hot Topics from Sponsors

- Recorded Food Safety Fridays

- Recorded Food Safety Essentials

- Recorded Hot Topics from Sponsors

- Food Safety Live 2013

- Food Safety Live 2014

- Food Safety Live 2015

- Food Safety Live 2016

- Food Safety Live 2017

- Food Safety Live 2018

- Food Safety Live 2019

- Food Safety Live 2020

- Food Safety Live 2021

- Training ˅

- Links

- Store ˅

- More

Advertisement

Featured Implementation Packages

-

SQF Implementation Package for Pre-processing of Plant Products - Edition 9

This comprehensive documentation package is available for immediate download and... more

-

BRCGS (& FSMA) Food Safety and Quality Management System for Food Manufacturers - Issue 9

This comprehensive yet simple Food Safety Management System Package contains EVE... more

SQF from Scratch: 2.3.2.6 Finished Product Labels

Jan 26 2021 11:01 AM | Simon

SQF SQF 2.3.2.6 finished product labels

2.3.2.6 Finished Product Labels

As we consolidated our raw material documentation in the last post, it occurred to me that the mention of “accurate finished product labels” was a bit more labor intensive than the brief aside the code gave it. Product labels are consultant bread-and-butter because the legislation is vast and product specific, and because frankly, the data shows that the industry is bad at making sure product labels are accurate! With that in mind, let’s talk though both some practical ways to maintain control of the content of the labels and the products therein, as well as how to make sure we can demonstrate that control for anyone who wants to verify.

The code:

2.3.2 Raw and Packaging Materials

2.3.2.6 Finished product labels shall be accurate, comply with the relevant legislation and be approved by qualified company personnel.

Also

2.4.1.1 The site shall ensure that, at the time of delivery to its customer, the food supplied shall comply with the legislation that applies to the food and its production in the country of use or sale. This includes compliance with legislative requirements applicable to maximum residue limits, food safety, packaging, product description, net weights, nutritional, allergen and additive labeling, labeling of identity preserved foods, any other criteria listed under food legislation, and to relevant established industry codes of practice.

Also

2.6.6.1.ii finished product is labeled to the customer specification and/or regulatory requirements.

Also

2.8.1.8 The site shall document and implement methods to control the accuracy of finished product labels (or consumer information where applicable) and assure work in progress and finished product is true to label with regard to allergens. Such measures may include label approvals at receipt, label reconciliations during production, destruction of obsolete labels, and verification of labels on finished product as appropriate and product change over procedures.

What’s the point? How is this making our product safer?

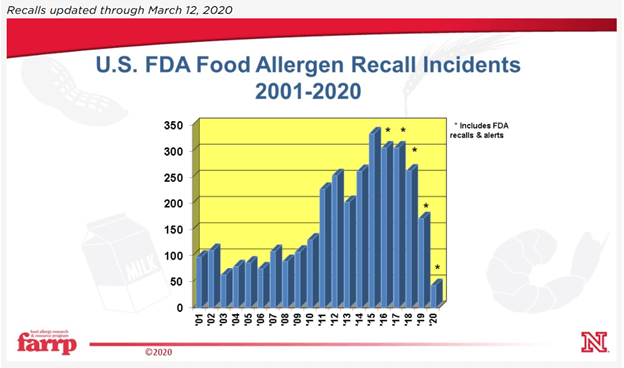

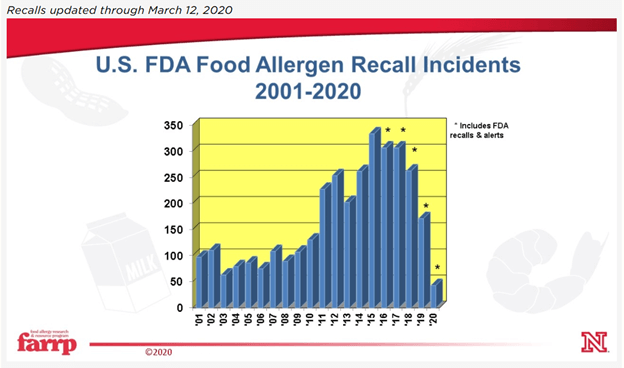

Here in the U.S., the recall statistics for inappropriate product labeling have been pretty damning.

Both FDA and FSIS regulated foods name undeclared allergens as a leading cause of manufacturer recall. First, because an undeclared allergen has the potential to be life threatening for people with severe allergies. Second, because it’s an easy mistake to make. Companies focus so hard on making sure that food is protected from biological and physical contamination that avoiding the introduction of another, otherwise safe, food ingredient requires a different approach to hazard prevention.

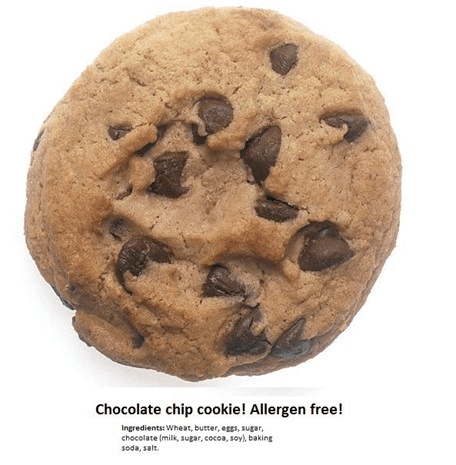

It’s odd to think that some of the foods sold in a facility can be just as much a hazard to consumers as material known to be contaminated with pathogens.

There’s a variety of ways that allergens can end up in products that are addressed throughout the code. In this article we’re going to focus on making labels in the first place, since an alarming number of recalls are due to unlabeled allergens, rather than a mix-up at production.

There’s another ROI here if making sure an accurate ingredient declaration isn’t enough of a motivator. Labels that fail legislative requirements or contain typo’s at worst put the company at risk, and at best make the product look low quality.

What am I being asked to do?

2.3.2.6 Finished product labels shall be accurate, comply with the relevant legislation and be approved by qualified company personnel.

So how are food labels typically made?

Original art concepts can come from anywhere, but eventually some sort of art house is going to generate a proof of the label. A (nowadays) digital file that includes the artwork superimposed on packaging specific details like die lines.

A new label process might look like:

- The sales and marketing team meets with an art house that specializes in food labels, and may or may not also be the printer of the packaging.

- They create concepts, and the food packaging experts at the art house keep placeholders for required regulatory content like nutrition, net weights, ingredients, etc.

- Eventually all of the product details for those nutrition panels etc. are provided and added to the artwork.

- The art house submits a “final” draft/revision of the proof to the company to approve before sale.

- The SQF practitioner or designee verifies the accuracy of the legal and food safety portions of the label, or approves the consultant doing it on their behalf.

The code specifies that the labels are “approved”. Now, at a 2-person company, we might be able to show an auditor the email to the art house that says “Joe has approved this revision” (assuming it’s saved and filed). But in larger groups, a more formal system is going to serve us better. The emails quickly get cluttered when the practitioner has actually approved the last 6 versions while the marketing folks kept debating whether the text should be taller or shorter.

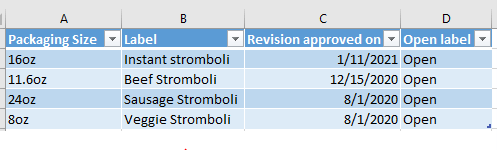

The approved “final” labels will need to be organized in a register eventually, either as part of the raw material and packaging specifications, or as a stand-alone register. In a company with multiple products using the same kind of packaging, a separate register is often most beneficial. It prevents either enormous packaging specifications or dozens of duplicated ones.

To demonstrate the label was approved before use, the practitioner can sign and date either a printed copy, a cover sheet, a change management record like the one we introduced in 2.1.3, or “sign” the register/database by including an “approved by” column (note, some auditors don’t like this without a digital certificate process [i.e. password protected signature], however I’ve had success selling the effectiveness of this system as long as the reviews were real and I could produce the person who signed).

If you need help creating an index that would open digital copies of the approved label “proofs”, there are some examples in this video series here: Excelling at Food Safety.

REVISION/VERSION CONTROL

Above we discussed creating and approving new labels, but it’s not going to end there! Year after year products will be changing art styles, ingredient suppliers, and formulations. Many of these will require label updates accordingly, and suddenly there are multiple versions of the same label for each product.

While revision control requires extra inventory management in most circumstances, when the new labels have something like an allergen that was added to the product, additional control becomes necessary.

Example: a new chocolate chip cookie supplier uses walnuts in their dough formula. If the new cookies are placed in old packaging on hand that doesn’t declare walnuts, there is now a dangerous hazard for anyone with that allergy.

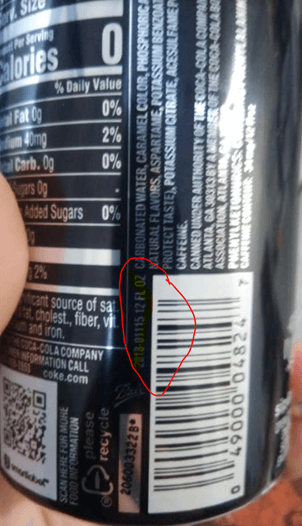

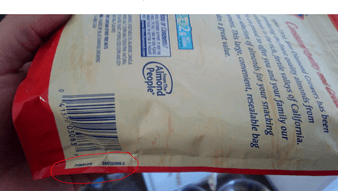

The best form of revision control is actually printed on the label somewhere. That way an operator/inspector can verify whether the labels on hand are the current revision approved in the registry. These can often be found in inconspicuous places on packaging:

Choose any revision labeling scheme that makes sense in the facility. I always appreciated a simple one that also shows when the label was approved such as yymm## (A two-digit year, two-digit month, then some sort of serial count of how many labels had been approved so far during that month, First being 01, second being 02 etc.).

With each version of the label created, use a new designation and have a system in place to determine which revisions are okay to continue using if they’re on hand. New packaging/label orders should only be of approved revisions (which can be inspected and compared against the registry of approved label proofs). Older label revisions that are no longer okay to use (such as the allergen example above) need to be isolated and controlled.

Revision control is often where the “approved label” process can fall apart. Facilities often have the first label approved in their product development files, but making sure that nothing important changes when the artwork is updated is one of the most tedious and error laden tasks asked of label reviewers.

Remember, every single time artwork is revised, review all aspects of the label. The art house may not have perfect revision control either and I could buy a lot of beer if I had a dollar for every time my clients requested a minor revision only to find something random had changed on the next proof.

How will this be audited?

I’ve encountered a few different approaches to auditing this requirement.

- The auditor will grab a label off the floor and request to see the specification and the approved copy.

- The auditor will request to see the register of label proofs and check that there is some sort of signature approval for them, and may later confirm one of them matches what’s on the production floor.

- The auditor will bring in a product they bought on the way there (rare but a fun tool since they can ask for traceability etc. on the same item)

- There is a register of labels, either in paper or digital, but there’s nowhere to see when they were approved or by whom.

- Everything looks good…for primary packaging labels. But records aren’t being kept for case labels, boxes, or film overwraps that also contain legal or safety related information.

- There is no evidence of revision control for labels with allergen statements and the practitioner can’t say for sure that the formula has never changed.

- The person responsible for checking labels for accuracy/correct revision when a new order arrives has no idea where the register of approved labels can be found.

And even if you do catch a label mistake on arrival, the company isn’t going to be thrilled that a lack of upfront review resulted in pallets of unusable packaging.

Author Biography:

Austin Bouck is a food safety consultant in Oregon, USA. You can find more food safety resources and discussion on his website, Fur, Farm, and Fork, as well as contact information for consulting services.

0 Comments