- Home

- Sponsors

- Forums

- Members ˅

- Resources ˅

- Files

- FAQ ˅

- Jobs

-

Webinars ˅

- Upcoming Food Safety Fridays

- Upcoming Hot Topics from Sponsors

- Recorded Food Safety Fridays

- Recorded Food Safety Essentials

- Recorded Hot Topics from Sponsors

- Food Safety Live 2013

- Food Safety Live 2014

- Food Safety Live 2015

- Food Safety Live 2016

- Food Safety Live 2017

- Food Safety Live 2018

- Food Safety Live 2019

- Food Safety Live 2020

- Food Safety Live 2021

- Training ˅

- Links

- Store ˅

- More

Advertisement

Featured Implementation Packages

-

Consultants 10 Site License Package

This is a great value package for consultants providing GFSI implementation serv... more

-

BRCGS Food Safety and Quality Management System for Food Manufacturers - Issue 9

This comprehensive yet simple Food Safety Management System Package contains EVE... more

SQF-2.3.2 Raw and Packaging Materials

Oct 26 2020 12:21 PM | Simon

SQF 2.3.2 raw materials packaging materials

2.3.2 Raw and Packaging Materials

Hello again practitioners, I know we’ve had some challenges so far, but now we have the management buy-in, time, resources, and motivation to get all of our SQF materials together! The next thing we need to do is source raw materials and put together some documentation for them!

The best foods start with the best ingredients, or in the world of manufacturing, the most consistent products start with the most consistent ingredients! As part of a careful and well thought out product development process, our teams have approved formulas, processes, recipes, and risk assessments that were based on ingredients that met certain criteria.

However, buy-in is going to disappear rapidly if it turns out…

- The “raising agent” R&D used was actually baking powder, not soda, and so we can’t use the 400 lbs of material that just arrived.

- The 1 in (2.54cm) diced carrots aren’t going to reach the required temperature in the retort because the cycle was designed for a ½” dice.

- The labels for the muffins say “gluten free” when they, uh, aren’t.

The code:

2.3.2 Raw and Packaging Materials

2.3.2.1 Specifications for all raw and packaging materials, including, but not limited to ingredients, additives, hazardous chemicals and processing aids that impact on finished product safety shall be documented and kept current.

2.3.2.2 All raw and packaging materials and ingredients shall comply with the relevant legislation in the country of manufacture and country of destination, if known.

2.3.2.3 The methods and responsibility for developing and approving detailed raw material, ingredient, and packaging specifications shall be documented.

2.3.2.4 Raw and packaging materials and ingredients shall be validated to ensure product safety is not compromised and the material is fit for its intended purpose. Verification of raw materials and ingredients shall include certificates of conformance, or certificate of analysis, or sampling and testing.

2.3.2.5 Verification of packaging materials shall include:

i. Certification that all packaging that comes into direct contact with food meets either regulatory acceptance or approval criteria. Documentation shall either be in the form of a declaration of continued guarantee of compliance, a certificate of conformance, or a certificate from the applicable regulatory agency.

i. In the absence of a certificate of conformance, certificate of analysis, or a letter of guarantee, tests and analyses to confirm the absence of potential chemical migration from the packaging to the food contents shall be conducted and records maintained.

2.3.2.6 Finished product labels shall be accurate, comply with the relevant legislation and be approved by qualified company personnel.

2.3.2.7 A register of raw and packaging material specifications and labels shall be maintained and kept current.

What’s the point? How is this making our product safer?

Our entire food safety management system, and more specifically our food safety plan, is based on a lot of assumptions. Food scientists recognize those assumptions and see food more often as chemistry than art. Knowing exactly what will come out depends on what goes in.

Some of the criteria are functionality and quality based. For example, most people purchase regular sized marshmallows to make s’mores, and a buddy showing up with miniature marshmallows may not have an easy time manufacturing their dessert.

It could also be problematic if the next shipment of marshmallows was pink or something.

SQF is less interested in quality or marketing needs, though we should certainly use this system to help define what we need to make the product successful. For our audit, what we’re primarily concerned with are criteria that will impact the safety of the product, rather than its performance. We want to make sure that any variation in the product won’t suddenly make it dangerous.

What am I being asked to do?

First things first, we have some familiar housekeeping.

2.3.2.3 The methods and responsibility for developing and approving detailed raw material, ingredient, and packaging specifications shall be documented.

As we’ve seen before this particular language is going to be repeated over and over again in the code in the same format:

“The methods and responsibility for [SQF code portion] shall be documented and implemented.”

This is a throwback to the food safety management system. The “methods and responsibility” is the document on hand that describes what the company intends to do and who is going to do it. It will describe what the management system looks like at that specific facility and which individuals will make sure the process is followed and documented (SQF practitioner or designee typically).

Key words: the methods should be “documented”, the policy exists, and “implemented”, evidence/documentation is available to demonstrate it is being followed.

As we go through the rest of this section, we’ll explore methods to maintain systems that support the code and create evidence/documentation. Make sure to also document the process itself and who owns it rather than rely on tribal knowledge to keep the system running.

2.3.2.1 Specifications for all raw and packaging materials, including, but not limited to ingredients, additives, hazardous chemicals and processing aids that impact on finished product safety shall be documented and kept current.

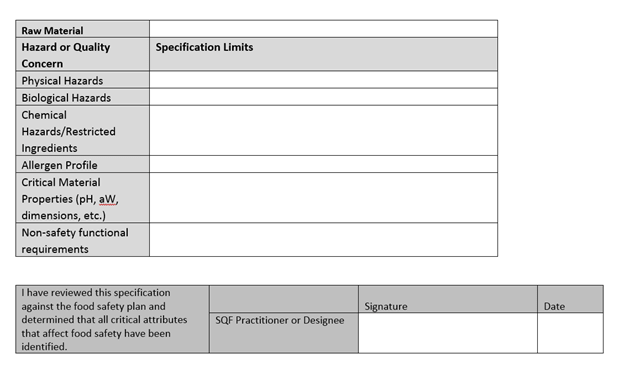

So, what is a specification? We’ll see them again for finished goods later in the code. A specification should be a description of the critical criteria that needs to be met to make sure the products are safe.

These specifications will likely be determined, again, by the hazard analysis in the food safety plan. They’re there so that when sourcing materials we know what to look for and what is and is not flexible.

Early season or late season fruit? Probably flexible and less important in the hazard analysis. Contains salmonella? Probably an important distinction.

SQF lists several examples of critical criteria in their guidance documents, so those are the ones auditors will be expecting to see:

- Limits for relevant pathogens or microorganisms

- pH

- Water activity

- Chemical or physical contaminants (e.g. pesticide residues or processing chemicals)

- Presence or absence of allergens

Ways to keep “specifications” on hand

A common one is to use those provided by the vendor. This can be audit friendly and save you some time, but inevitably there are a few problems with this solution:

- The vendor may not have a “specification” that meets your needs. Either it’s just advertising material that’s too generic, or they literally don’t have one because it’s a non-GFSI company that isn’t required to make something like that.

- The vendor may have a specification, but they aren’t going to provide an updated one annually. The packaging they sell generally doesn’t change nor do many crops.

- The vendor just isn’t responsive when asked for documentation, either because they don’t have it or the customer doesn’t buy enough from them.

- The vendor doesn’t include criteria critical to the food safety plan in their specification.

I know, that’s breaking our golden rule.

The issue is that while a practitioner can be amazing and document anything that happens on site, it doesn’t matter if they have an unresponsive vendor. And despite what some consultants will say about dropping vendors, a little jam company doesn’t have a ton of buying power to demand special documentation. That company’s supplier may be the only one feasible to buy from due to pricing or geography.

SQF lists specifications before vendors in the code because in theory companies need to know exactly what to buy before looking for a source. This is true when finding new vendors, but for new product or ingredients, normally they’re created with test materials from a vendor, and a hazard analysis is performed after finalizing a source.

That means that in a way, we’re addressing section 2.4.4 (approved supplier program) first, because we won’t be able to source a material from an unapproved supplier, whether we have a specification or not.

So, if we have to talk to a supplier, we might as well try to cover all of our bases at once. In that spirit, it sometimes makes sense to combine these elements.

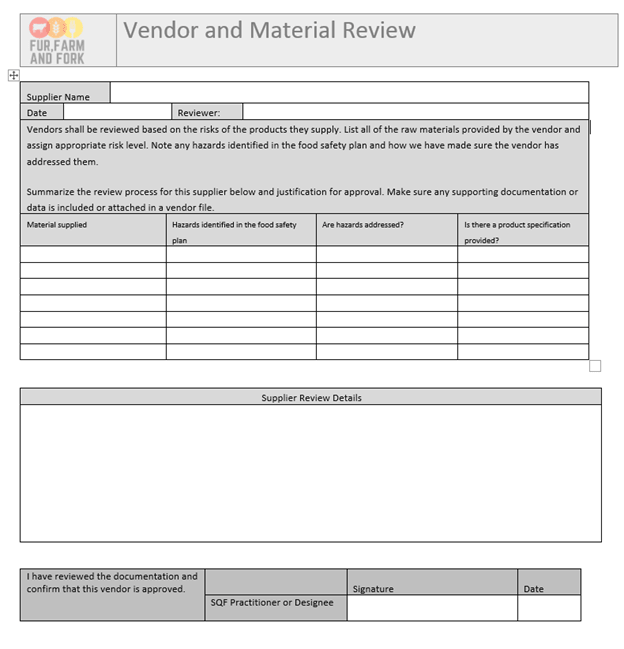

In a larger company with multiple suppliers for a single ingredient, independent raw material specifications may be more helpful, but for many small businesses we can try to knock these elements out together.

Using this example, we can review vendors, list out the critical criteria outlined in our food safety plan, and provide a narrative explanation of the specifications and documents they were able to provide to confirm them. I tend to favor narrative risk assessments for supplier review, because it allows you to base approval status on your own specific history with the supplier, and allows for approval even if there’s missing information.

However, if a vendor does not provide a specification, then one will need to be created regardless.

2.3.2.2 All raw and packaging materials and ingredients shall comply with the relevant legislation in the country of manufacture and country of destination, if known.

This is really an extension of 2.4.1. After all, our products won’t comply with legislation if the ingredients didn’t comply. We’ll dig into the systems to make sure things are on the up-and-up in 2.4.1. For this line item, just avoid buying anything sketchy. No inappropriate suppliers (looking at you, backyard butcher shops), no materials that can’t normally be sold legally finding their way into inventory at a discount, no attempts to use state or country boards to circumvent a particular requirement, etc. The supplier review process will address documentation to support this clause.

SQF specifically calls out suppliers who may use food labeling across country borders that does not comply with the country of sale. This is a really common issue for importers and one to watch out for. Consumer facing labels need to comply with the regulations of the country in which they’re presented for sale.

2.3.2.4 Raw and packaging materials and ingredients shall be validated to ensure product safety is not compromised and the material is fit for its intended purpose. Verification of raw materials and ingredients shall include certificates of conformance, or certificate of analysis, or sampling and testing.

This is tricky, because SQF likes to play fast and loose with “validation” and “verification” language in the code. For this particular section, to make it even more confusing, let’s quote the guidance document:

Validation is testing over and above daily monitoring to ensure that established food safety limits are effective, i.e., they achieve the desired results, so that the supplier can have confidence that the product and process are safe. Validation methods will vary depending on the risk to finished product safety. Validation for low risk materials may include certificates of analysis or certificates of conformance, provided by a trusted vendor. For high risk materials, testing and analysis is required for validation, and must be carried out annually (refer to 2.5.2). For food-contact packaging material, this may include testing or assurances for potential chemical migration to the food product.

They then later ask us to “verify” in 2.3.2.4 using the same criteria they listed for “validation”.

Here’s the deal, at the end of the day, we can remain consistent by defining these terms this way:

Validation: The research and testing done to prove that, if everything works the way we want it to, it will achieve the intended food safety result. We validate our specifications, target limits, and “the plan”.

Verification: A periodic check to make sure all of our assumptions are still holding true.

Use the food safety plan and product development process to “validate” raw material specification requirements and make sure that as written they will work. We need to validate both the specification and the approval criteria. The food safety plan should indicate what’s needed, and the specification maintenance document should state how you’ll use that plan to make sure that what you source meets the needs of the plan.

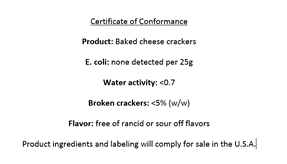

Then, with existing suppliers and raw materials, “verify” that the ingredients are still complying with the specifications. This may mean that we got a certificate of analysis from a supplier with our first shipment saying they were E. coli free. So, we decided to approve them. But once in a while we should ask for another one, to “verify” that the supplier is still providing an E. coli free product, or if the juice concentrate is still that same pH it was a year ago when we made the plan. Minimum interval of annually.

Let’s clarify some other definitions here that are commonly used when discussing supplier approval, and describe how useful they are to us:

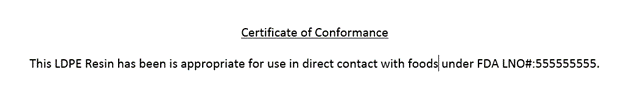

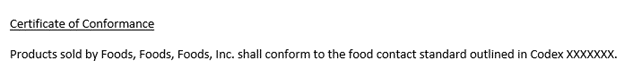

Certificate of Conformance: This is similar to a supplier specification, it’s typically the suppliers “finished good specification”. The Parameters that they say they the product will meet based on their own internal testing/monitoring. This is different from a “certificate of analysis”, which will include actual test results. A certificate of conformance may be issued in general, or issued for every lot when it is released (e.g. based on testing that was performed, the material will conform). These can sometimes be used as a supplier specification if it happens to have everything you need. It could list specific criteria like this:

Or for packaging it may be something like this:

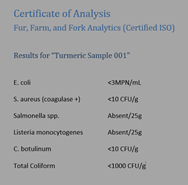

Certificate of Analysis: A certificate of analysis covers actual test results for a particular sample. Sometimes they’ll be for each individual lot of product, other times they may be the suppliers’ own validation testing. Typically, a certificate of analysis will have a letterhead from the laboratory that performed the work, indicate what samples were tested and show the actual test results. It might look something like this:

Letter of guarantee/declaration of continued guarantee of compliance: Letters of guarantee were covered in the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (USA) to protect manufacturers from upstream food fraud. Per the FDA:

Section 303, paragraph © of the Act states that no person shall be subject to the penalties of subsection (a)(1) for having received, or proffered delivery of, adulterated or misbranded food additives if he has established a good faith guarantee from whom he received the articles. This paragraph was included in the 1958 amendments to the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act and remains the legal basis for the "letter of guaranty" supplied by many manufacturers to their clients.

This can be part of ensuring materials are compliant with legislation. FDA provides language used in these letters here.

So, for us to meet the requirement of 2.3.2.4

- We should make sure we have either tested the material or requested verification from the supplier that it is still meeting our validated specification.

- Do this at an interval appropriate to the amount of risk associated with the hazard.

i. Certification that all packaging that comes into direct contact with food meets either regulatory acceptance or approval criteria. Documentation shall either be in the form of a declaration of continued guarantee of compliance, a certificate of conformance, or a certificate from the applicable regulatory agency.

i. In the absence of a certificate of conformance, certificate of analysis, or a letter of guarantee, tests and analyses to confirm the absence of potential chemical migration from the packaging to the food contents shall be conducted and records maintained.

Food packaging is sort of in a separate category, and will normally give the most trouble in terms of getting things from vendors. These companies may make food contact packaging, but here in the U.S. they aren’t audited, so it’s on the practitioner or procurement team to find someone who knows what needs to be covered.

The purchaser can either perform chemical migration testing themselves at an appropriate interval (expensive), or work to get that documentation together and keep it current. Auditors tend to be a bit laxer on this as long as there is something recent on hand to show them.

2.3.2.6 Finished product labels shall be accurate, comply with the relevant legislation and be approved by qualified company personnel.

….You know what, we’ll address label review in the next SQF from scratch. It’s a big enough topic to merit its own article. Sorry to make you wait!

2.3.2.7 A register of raw and packaging material specifications and labels shall be maintained and kept current.

To make a register of these specifications and label reference materials, check out Making sense of the SQF code: so what the heck is a “register?”

Make a list of the specifications and label reference materials, organize it in a way that helps keep it organized and up to date.

How will this be audited?

I’ve encountered a few different approaches to auditing this requirement.

- The auditor during the site tour will identify 3 different ingredients, some packaging and some ingredients, and then request to see specifications for those materials followed by verification documentation.

- The auditor will request to see the specification register first, then select materials at random to review the documentation.

- The auditor will request verification of ingredient specifications and testing while reviewing the hazard analysis (and supplier preventive controls in the U.S.).

- There is a specification for the material. Either

- One the site created itself, reviewed within the last year.

- One from the supplier that has sufficient information, and has at least been reviewed by the site within the last year (even if the supplier didn’t update

- There is verification documentation of the material, either:

- Test results from an on-site sampling program.

- Testing performed by the supplier and provided at a minimum annually, more frequently for higher risk criteria (like microbiological results).

- For food contact packaging, either testing or some kind of documentation from the supplier (like a letter of guarantee or certificate of conformance) indicating it’s appropriate for food contact.

- A narrative review of the supplier that explains how the site verified the information without the need for specific testing (e.g. maybe the supplier’s continued SQF certification ensures they would comply with their own finished good specifications; it can be worth a shot)

- The verification documentation matches and has been conducted at the intervals specified in the SOP. (Say what you do and do what you say).

- Outdated or unprofessional looking “specifications” from a supplier. A copy of their webpage from 3 years ago doesn’t look legit. Keep in mind, a signature and date showing that the practitioner “reviewed” this document within the last year will actually go a long way to making these sufficient.

- Testing or documentation required by the SOP that are outdated or not performed for all of the materials, new ones, or ones purchased infrequently.

- Materials purchased from brokers or distributors that have little to no information from the actual manufacturer of the product when needed.

- Using one document for everything. A single CoA might be able to be used for everything once at initial vetting…. but it looks like something’s missing, and there probably is.

It can be worth it though, especially when we find out that our suppliers aren’t as consistent as we thought.

Many companies without SQF will make sure they’re sourcing ingredients that don’t have common pathogens, but without the code they may forget risks associated with packaging and other subtle changes. Taking the time to “specify” what we need may be the difference between getting a consistent ingredient or one that caused an accidental recall.

Author Biography:

Austin Bouck is a food safety consultant and manufacturing supervisor in Oregon, USA. You can find more food safety resources and discussion on his website, Fur, Farm, and Fork, as well as contact information for consulting services.

0 Comments