1 votes

1 votes

Yes, Every Food Operation Can Use SPC

SPC Statistical Process Control

If SPC is not a term used by your quality department, it should be! SPC, or Statistical Process Control, is a data-based methodology for monitoring and adjusting operations in real-time to meet control standards. Not only is it a useful tool for optimizing your process, but it can also be the difference between success or failure in many of today’s audits. So, whether you want to reduce waste, yield a more consistent product, stay competitive, or (most likely) all of the above, SPC is one acronym you need to know. What you don’t need, however, is a degree in statistics or new monitoring equipment to implement a basic program. This is good news for small operators, who may be wondering whether their quality program can ever meet expectations like those of GFSI.

The short answer for any firm, I believe, is yes. The long answer involves a self-evaluation of time and resources, and whether upping your quality game is worth the effort of taking on some new tasks. Do note that expectations may vary, and this piece is based on my experience alone, but I’ll lay out few of the basic necessities for understanding and utilizing SPC.

Essentially, SPC boils down to your ability and willingness to monitor and adjust your process at regular intervals, if not continuously. Continuous monitoring, while it is the gold standard, is not necessary in order to have an SPC program, and is not possible for many processes, as the equipment can be prohibitively expensive or even nonexistent. You may have a mix of measurements taken continuously by machine and others taken by-hand at some specified frequency. This is common and can even prove more effective than complete automation, as human and machine monitors both have strengths and weaknesses that work well when combined.

When there is a process for which you must monitor quality (or safety) of product and continual measurement is not feasible, you must determine the frequency of monitoring appropriate for that checkpoint. I like to use a documented risk-assessment for this, and you’ll find most auditors will be looking for this too. The documentation, though, does not stop there. The monitor must ensure that real-time measurements are recorded and checked in case an adjustment needs to be made. This assessor can be the monitor or a secondary supervisor, but they must be fully trained on the procedures (they should also have a copy of the control limits on-hand, either posted at the monitoring stations or directly on the recording sheet/device). Beyond this, most audits will also require proof that a responsible validator reviews each record afterwards, and this person should be trained in at least basic SPC to understand how to identify sources of variation, for example detecting special vs. common cause. Common cause variation is the random “noise” you expect to see from your process, reducible by process improvements, while special causes represent a pattern or outlier beyond the scope of normal functioning which signal a specific, unusual issue, like machinery malfunction. Both result in potential losses, both from a monetary and product quality standpoint, and so the study and control of variation is very beneficial.

Training courses and self-teaching materials on SPC are widely available. Whether you prefer to enroll in a short course (look for one to fit your audit scheme or regulatory body; for example Alchemy Academy offers an online SPC course with an SQF focus1), consult a textbook (I recommend Statistical Process Control for the Food Industry: A Guide for Practitioners and Managers by Lim and Antony2), or use free online materials (IFSQN published a wonderful webinar on SPC to Youtube in 20173), there are a myriad of options to aid you.

All in all, this system requires manpower of at least two to three trained individuals, and additional staff as needed depending on the process scope. Management should task themselves with ensuring that the monitor has enough time to effectively check, record, and review each checkpoint without exhaustion, or this becomes a meaningless exercise and those resources could be put to better use.

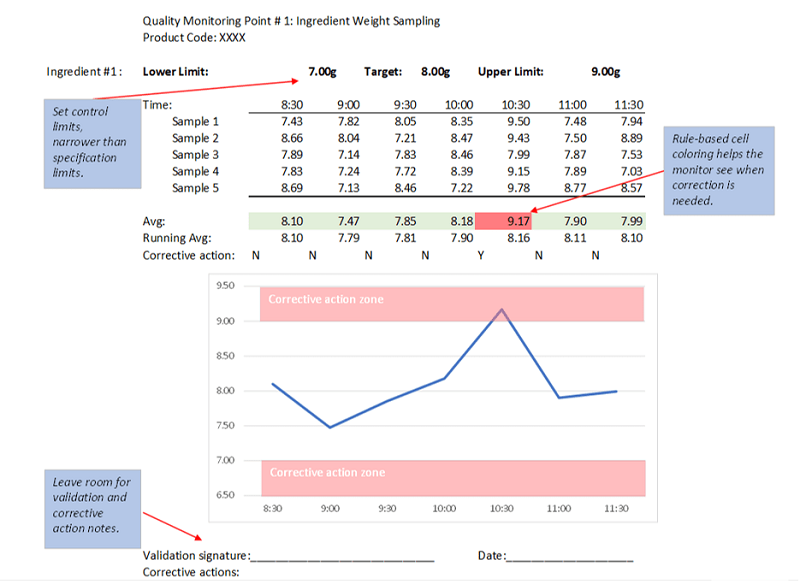

I will outline one example of a successful manual SPC system. In a simple process, pre-cooked, refrigerated ingredients are dispensed into a package, each with a target weight, to be blast-frozen and sold individually. For each one or two manufacturing lines, one technician continuously walks the floor and is responsible for checking that the automatic monitoring machines (weight checker, metal detector, etc.) are on, operational, and properly tuned at the beginning, end, and regular intervals throughout the shift (the technical specifications or a validation study should be used to choose this frequency). They also perform most of the manual checks at validated frequencies, for safety and quality points including ingredient and mixing weights, temperatures, and date codes. Of course, checkpoints will vary and are specific to each process, but you may have noticed that some of these are “pass/fail,” like metal detection and date coding, but others are numeric in nature. Most checkpoints require some special training – for monitors, this includes equipment verification (e.g. checking the calibration of scales and thermometers, which should be done prior to the shift and can even be a separate job as long as a chain of communication is present), a brief overview of what SPC means (which could be as simple as re-phrasing the first sentence of this piece), recording procedures, interpreting results, and making corrections in real-time. For more sensitive checkpoints, like ingredient weights in the process described here, it is handy to provide digital recording templates for each record. Even if it is just a simple spreadsheet, this can be made to map directly to a kind of “pseudo”-control chart that will show the monitor where their record falls in relation to the specification (see example).

I have found this to be an extremely useful tool for small-scale operations, and if used properly, it can be the key to prove that real-time process monitoring occurred, even when continuous monitoring is out of reach. I have also found these charts to be helpful in performing more advanced statistical analysis for continuous improvement projects.

Finally, for an after-the-fact validator, these charts provide time-saving visual cues. Though not every producer may be able to use digital recording methods, like a station near the line with a computer or tablet, this is just one example of how strategically allocating resources can compensate for lack of in-line equipment, and is not the only way to do SPC on a budget. When in doubt, before your first audit, consider requesting a practice audit or hiring a consultant to evaluate whether your SPC system meets the chosen standard. I will leave you with this, if you are on the fence about diving into SPC – all you really need is a team willing to learn and adapt.

1. https://academy.alch...ol-fundamentals

2. Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.c...y/dp/1119151988; or read an excerpt from Wiley: https://media.wiley....19151988-17.pdf

3. https://www.youtube....h?v=s4mGHVzDxLg

About the Author:

Stephanie Cunningham

A foodie with 6 years of experience in Quality Assurance and a B.S. in Food Science from Penn State, Stephanie is an avid food safety advocate with a passion for reading, writing, and encouraging people to think about their role in assuring safe food for everyone. She is currently working on a Master’s Degree in Applied Data Science and feels that there is a need for more tech-centric solutions in the food industry.